[Analytics] Coronavirus turns Teflon Thailand’s wealth gap into a economic chasm

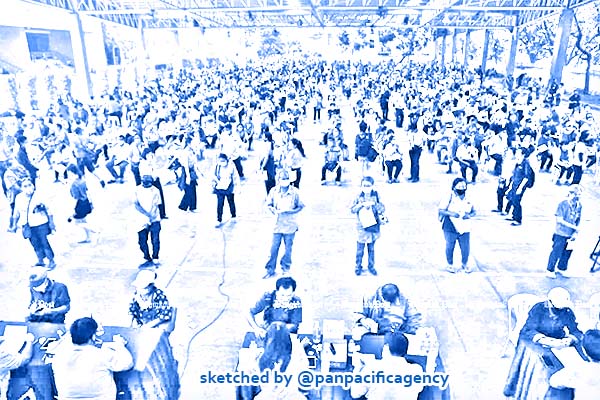

People wait to submit their complaints about the 5,000-baht cash handouts at the Public Relations Department on Soi Ari Samphan where social distancing was arranged due to the coronavirus outbreak. The previous venue was located underneath an expressway near the Finance Ministry. (Photo by Arnun Chonmahatrakool). Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

As Covid-19 eats into exports and tourism, the gap between rich and poor in one of the world’s most unequal countries is only getting wider. With both the lower and middle classes now facing ruin, ‘Teflon’ Thailand’s reputation for weathering financial crises is feeling the heat like never before. Vijitra Duangdee specially for the South China Morning Post.

On a roadside in a mixed Bangkok neighbourhood stands a shiny metal box – a “Pantry of Sharing” – where the haves in one of the world’s least equal countries can leave food for the have-nots, the ranks of whom are bulging as the coronavirus lays waste to the Thai economy.

Each day, maids from the grand mansions nearby drop off an inventory of essentials – eggs, noodles, milk, sugar and water, sometimes a bag of mangosteens or rambutans – charity for those suddenly jobless.

Opposite the pantry, Sumarin Boonmee says her life has been pitched into uncertainty since she was put on unpaid leave from her job at a supermarket three months ago.

“I have no idea when I can go back, so I am selling meat skewers here for a little income,” she says, tending to a tabletop grill.

She is a member of the Leelanut community, a slum of day workers and stallholders living under corrugated roofs amid cluttered walkways beside a mucky canal.

The community is flanked by wealth – gated villas, wood-panelled cafes, condos and high-end salons. It is a hangover from old Bangkok, before money poured in and breakneck development airbrushed most of the poor from prime areas of the city.

There are millions of newly unemployed like Sumarin, according to the Thai government, which last Sunday secured a near-US$60 billion stimulus package – the largest in Thai history – to resuscitate an economy flatlined by the virus.

Bangkok locked down in late March. It is stuttering back to life. But jobs have been shredded, especially for those who depend on daily wages or low-paid jobs as cleaners, motorbike drivers and security guards.

At the pantries, most are embarrassed for being forced to turn to handouts.

“I’m just taking enough for now, so that others have something too,” says Suthep, a 49-year-old truck driver, taking a red-bean bun and a carton of milk for his granddaughter.

Thailand’s economy leans heavily on exports and tourism and has been cruelly exposed by the impact of the virus, which has closed international travel and shrunk global demand.

Now the “Teflon Thailand” tag, earned for resilience through financial crises, disasters and cycles of political turmoil, is being tested like never before.

METRES AWAY, WORLD’S APART

There are now scores of pantries across Bangkok, lifelines for those in need but also rare connection points between the rich and the poor.

The pantry at the Leelanut community is filled twice daily by an heir to a large sock company, who lives 100 metres along the road in a grand house.

“My business has been hit hard by Covid. But I’m very lucky,” says Pinnarat Sethaporn, 51. “I really feel for those living hand-to-mouth at times like this.”

But it is not just the poor who are facing ruin. Middle-class workers are losing their office jobs, and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are bleeding cash, with knock-on effects on mortgage, car and school payments.

Between six and seven per cent will be hacked off annual growth, according to an IMF estimate.

The damage is already worse than the “Tom Yum Goong” crisis of 1997, when Thai banks overly leveraged with foreign debt collapsed, leading to a slump in the baht, white-collar redundancies and capital flight – problems that spread across the region and led to the Asian financial crisis.

“This time, those who will be hit the hardest are the low and middle classes,” says Pavida Pananond, an academic at Thammasat Business School in Bangkok.

“This crisis will further widen Thailand’s inequality.”

BILLIONAIRE TOWN

Thailand is a country of extremes. Its king is one of the world’s richest monarchs while business monopolies with deep political connections have carved extraordinary wealth for family empires spanning from beer and duty-free to shopping malls.

The country has 57 billionaires, according to the 2020 Hurun Global Rich List, the ninth most in the world with a combined wealth of US$135 billion – more than Singapore, Japan or France.

Only China and India boast more billionaires in Asia, according to the list by the Shanghai-based publishers.

In April, Prayuth Chan-ocha, the former general turned Thai prime minister, made an unprecedented plea for the tycoons’ help to float the economy and head off potential discontent with his already-unpopular administration.

Their widely publicised response has focused on retaining jobs and donating money and logistics to health care, generosity in a crisis which is unlikely to go unrewarded.

Prayuth’s appeal for help “offers these tycoons direct opportunities to do favours for the government”, says Pavida of Thammasat Business School.

“These tycoons know better than most what political favour can do for their businesses.”

But the billionaires have so far offered little in the way of major emergency funds, commitments to paying more tax or encouraging greater competition so SMEs can flourish in a monopoly-led economy they control.

In April, the Charoen Pokphand Group (CP Group), an animal feed-to-convenience store giant, said it had opened a US$3 million factory to make 100,000 face masks a day, to be gifted to health-care workers.

The firm, headed by brothers whose fortune Forbes in April estimated at a combined US$27.3 billion, also announced a US$30 million fund to tackle the Covid-19 crisis.

In a rare interview last month, family head Dhanin Chearavanont gave his views on ways to beat the crisis, urging the government to dole out low-interest loans, and open the doors to foreign expertise despite the massive job losses in the kingdom.

“Thailand needs around five million world-class talents to teach and lead Thais,” he told the popular investment page “Longtunman”.

“Give them Thai nationality to incentivise these great brains,” he added.

SLUMS AND CONDOS

At the Leelanut slum community, the focus is on finding jobs at home.

At her egg stall opposite the pantry, the formidable, crop-haired community head, Panita Khamnokdee, 56, says 30 years at the slum has given her a ringside view of Bangkok’s hyper-fast growth.

She recalls how untamed scrub turned into condos, international schools replaced scruffy flats and flashy cars began to ply the narrow road which runs beside her community.

Now at one end of the street a Thai celebrity gets out of a black van to go into a salon. At the other, office workers slurp down “Fat Burner” juices from a wellness cafe.

Local authorities want to take back the slum land and complete the gentrification of one of Bangkok’s most chichi postcodes.

Each year, her community is hemmed in further by new condos built by low-paid migrant workers, a snapshot of a city with two faces. “All I can do is look up,” Panita says. “I will never be able to afford one.”