[Analytics] Mideast war risks drawing in China and Russia, too

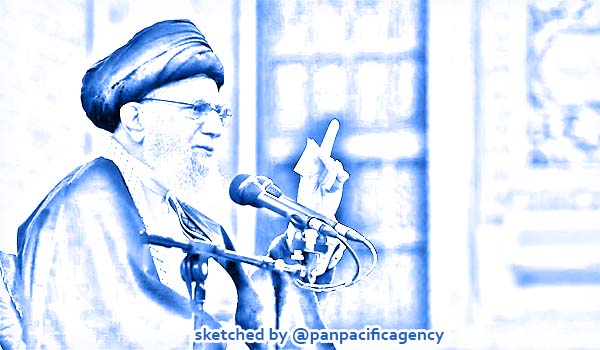

Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei vowed to take revenge for Soleimani’s killing. Photo: AFP. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

Beijing and Moscow have stood by Iran in the face of Washington’s belligerence. Now they must decide: how true a friend is Tehran, really? Cary Huang specially for the South China Morning Post.

America’s assassination of Iran’s second-most powerful commander, Major General Qassem Soleimani, has sparked fears of a war in the Middle East.

But it is not just the United States that risks getting drawn into a conflict, given the emerging Moscow-Beijing-Tehran axis.

Days before the US strike on January 3 – which also killed Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the head of Iraq’s Kataib Hezbollah militia group – China and Russia completed unprecedented joint military drills with Iran. Further evidence of growing ties can be seen in the four visits that Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif made to Beijing over the past year.

The Middle East was already a powder keg – with conflicts in Syria, Libya and Yemen, unrest in Iraq and Lebanon, as well as conflict between Israel and the Palestinians – but America’s most recent move has the potential to be more provocative and consequential for regional security than either the 2011 killing of al-Qaeda chief Osama bin Laden or last year’s assassination of Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

Just look at the anti-US fervour on show at the events held in Iran and across the region to mourn Soleimani for evidence of that fact.

Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei vowed to take revenge against the “criminals” who killed Soleimani, prompting US President Donald Trump to respond with a threat of his own: that “52 Iranian sites” would be “hit very fast and hard” if Tehran acts.

Tensions between Iran and the US have been ratcheting up ever since 2018, when Trump withdrew from a 2015 nuclear pact that had been agreed upon by Iran and five other nations, including China and Russia. The US president said he made the decision because Iran continued to build intermediate- and short-range missiles and drones.

China and Russia objected to the move and refused to participate in US sanctions against Tehran, leading Washington to see Beijing and Moscow as impediments to its effort to isolate the Iranian regime.

The escalating tensions have only really served to bring Tehran, Beijing and Moscow closer together, as Washington paints all three as its implacable adversaries. Indeed, they are cooperating to oppose American interests whenever and wherever possible, in the face of rising US antagonism.

Some observers have interpreted the four-day joint naval drill that the three held last month in the northern Indian Ocean and Gulf of Oman as symbolising the emergence of an anti-American alliance. The stretch of water where it took place, which includes the Strait of Hormuz through which about a fifth of the world’s oil passes, has immense geopolitical importance after all.

Amid US-led sanctions, China has become Iran’s economic lifeline alongside Russia, its main supplier of weapons and military technology. On December 31, Iran’s foreign minister made a joint pledge with his Chinese counterpart to stand together against “unilateralism and bullying”.

But Beijing does not want war in the Middle East, as the region plays a critical role in its cherished multinational trade plan, the Belt and Road Initiative. Under a 25-year programme signed in 2016, Beijing committed itself to an unprecedented US$400 billion of investment in the Iranian economy, including in infrastructure such as dams, factories, airports, roadways and Tehran’s subway system. Iran is also China’s most important supplier of oil – something that would be put at risk in a conflict.

Any action the Chinese side did take against US interests would also risk derailing trade talks, which finally seem to be moving forward after nearly two years of painstaking negotiations, broken promises and tit-for-tat tariffs.

Simply put, Beijing has too much to lose to justify any real action in support of Tehran. It also wants to maintain friendly relations with Saudi Arabia and its allies, many of whom are Iran’s arch enemies and fall under Washington’s security umbrella.

In comparison to China, Russia has been much more deeply involved in Middle East affairs since the Soviet era and has maintained closer relations with Iran. Despite their historical differences, Moscow and Tehran have worked as strategic allies in the conflicts in Syria and Iraq and have become partners in Afghanistan and post-Soviet Central Asia. Still, Russia’s top priority is in Eastern Europe at the moment, with fewer of its economic interests in the Middle East.

In recent years, China and Russia have deepened and broadened bilateral strategic and military cooperation against US security interests. The two have also joined forces at the United Nations to block any US-initiated Security Council resolutions, whether on the Middle East or elsewhere.

Both oppose Western-sponsored regime change in the region, and thus see Iran as a partner in countering US hegemony and the driving forward of a new, multipolar world.

Former US president Ronald Reagan once described the Soviet Union as an “evil empire”, while one of his successors, George W. Bush, lumped Iran, Iraq and North Korea together in his “axis of evil”. Now, Washington and Brussels call Beijing and Moscow “revisionist” powers, Tehran a “rogue regime” and the anti-US alliance they have begun to form an “axis of autocracy”. Such labels only really serve to unite the West’s opponents.

Moscow and Beijing might even be happy to see rising tensions between the US and Iran, as conflict in the Middle East would divert America’s attention away from challenging their interests in Eastern Europe and the Asia-Pacific. Both are also positioned to exploit such a conflict, if it did occur, to boost their clout and carve out spheres of influence in the region.

Yet without strong incentives for either to get directly involved in the squabble, they are more likely to limit themselves to anti-US rhetoric and giving moral support to Iran. After all, is Tehran really a true friend and diehard ally that Beijing and Moscow would be willing to go to war for? Or more an “ally of convenience” under the old realpolitik rationale that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”?

Cary Huang is a veteran China affairs columnist, having written on the topic since the early 1990s