[Analytics] Demise of S. Korea-Japan military agreement deals a blow to US Indo-Pacific strategy

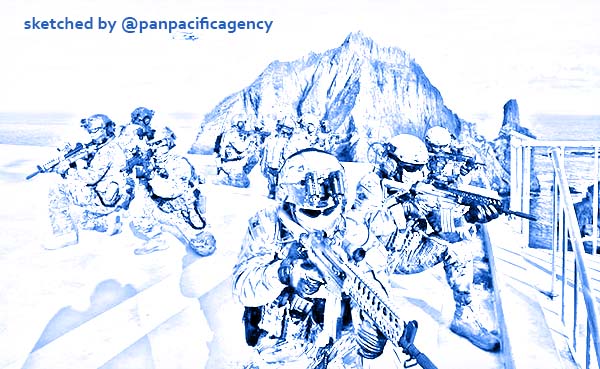

Members of South Korean Naval Special Warfare Group take part in a military exercise in remote islands called Dokdo in Korean and Takeshima in Japanese, South Korea, August 25, 2019. South Korean Navy/Yonhap via REUTERS. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

The General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA), signed by South Korea and Japan in November 2016, is set to fall apart as Seoul decided not to renew it amid the two nations’ heightened historical, trade and security disputes. Cheng Xiaohe specially for the Global Times.

Moon Jae-in’s government has its own reasons to do so. The agreement has been unpopular in South Korea. As early as in 2012, Lee Myung-bak’s government prepared to sign the deal with Japan, but it backed off at the last minute as the domestic opposition grew too strong. When Park Geun-hye gave the green light to the agreement in 2016, nearly 60 percent of Koreans opposed it, among which Moon’s Democratic Party was a leading voice. For President Moon, he just undid a move that he and his party once tried to stop but failed.

The agreement certainly helped facilitate intelligence sharing between South Korea and Japan, but Yonhap News Agency quoted a senior South Korean official as saying that “South Korea never used Japan’s intelligence in analyzing North Korea’s missile launches under the current Moon Jae-in administration.” As South Korea seeks good relations with both North Korea and China, the agreement, which mainly targets the two nations, has become less attractive in South Korea’s policy toolbox.

Japan has weaponized its trade with South Korea in order to redress the historical dispute, Seoul did not hesitate to reciprocate by picking up a fight in the security field. For South Korea, stopping the renewal of GSOMIA not only is less costly than resorting to trade countermeasures, but it can also force the US to intervene as Washington feels the pain caused with Seoul’s withdrawal from security cooperation.

The unraveling of the GSOMIA marks a new low in Seoul-Tokyo relations. Japan strongly protested against South Korea’s decision to scrap the agreement. As Soul and Tokyo dig in and prepare for a long-time fight, the spotlight is now on the US, which is the long-time ally of both South Korea and Japan.

Interestingly, even though the measures taken by both South Korea and Japan were directed at each other, their tit-for-tat tussle may produce some consequences the US does not want to bear.

First, the US effort to build strong security ties with South Korea and Japan will be in jeopardy. Since the end of the WWII, the US had painstakingly built a hub-and-spoke alliance system, in which the US alliances with Japan and South Korea constitute the bedrock of US security architecture in Northeast Asia. The alliance system had served US national interests well during the Cold War. In the post-Cold War era, the US continued to reinforce its traditional bilateral alliances and at the same time began to strengthen a horizontal connection between two alliances. As a result of the effort, the US, Japan and Australia introduced trilateral ministerial meetings into their security cooperation. For years, Obama administration had worked to build some trilateral security mechanisms with South Korea and Japan. In addition to the regular three-way policy consultations among themselves, the US government also encouraged Japan and South Korea to share intelligence.

The 2016 GSOMIA not only enabled Seoul and Tokyo to directly exchange sensitive information about North Korea’s missile and nuclear weapon program, but also paved the way to upgrade their security cooperation in the future. The demise of the GSOMIA will make their previous work worthless, undermine their capability to track North Korea’s development of missile and nuclear weapons and deepen their mutual suspicion that may take years to recover.

Second, the termination of the GSOMIA will bring into serious doubt the US Indo-Pacific strategy. As the Trump administration began to perceive China as a strategic competitor, it adopted the Indo-Pacific Strategy, which is based on a network of strengthened alliances and partnerships that span two regions of the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean. Many analysts criticize the strategy as an empty slogan. The worsening relations between South Korea and Japan will further fuel the criticism. The dispute escalation between two US allies and the absence of a strong intervention by the US reveals America’s diminishing leadership in Northeast Asia. If the US has a weak political will to lead or wants to avoid being dragged into allies’ brawls, it may struggle to lead a large number of allies and partners in carrying out the Indo-Pacific strategy. Many allies may feel they are not as important as they were.

President Moon asked Trump to get involved in the dispute when they met on June 30 in South Korea. Trump himself expressed his willingness to mediate if both South Korea and Japan wanted him to do so, nonetheless, the Trump administration failed to defuse the tension between the two allies. After South Korea decided to pull out of the GSOMIA, the US government raised its rhetoric, rebutting South Korean government’s claim that it had US understanding and registering its strong concern and disappointment. Morgan Ortagus, the spokeswoman of the US State Department, tweeted that the termination will make defending South Korea more complicated and increase the risk to US forces. Randall Schriver, US assistant secretary of defense for Indo-Pacific security affairs, called on the Republic of Korea “to recommit to GSOMIA and to renew that agreement.”

Obviously, realizing the grave consequences of the Seoul-Tokyo row, the Trump administration may step up its effort to bring the two allies to the negotiating table. More importantly, both South Korea and Japan have exercised self-restraint. Japanese government granted its first permit for a South Korea-bound shipment of the restricted chemicals in early August. The Blue House once said that it may reconsider its decision to end GSOMIA if Japan abandons its export curbs. With the US vigorous intervention, South Korea and Japan might find a way out of current friction, but it is not easy for both sides to reverse the trend.

The author is associate professor with the School of International Studies, Renmin University of China; a senior researcher with the Pangoal Institute.