[Analytics] Why Seoul-Tokyo reconciliation may be doomed

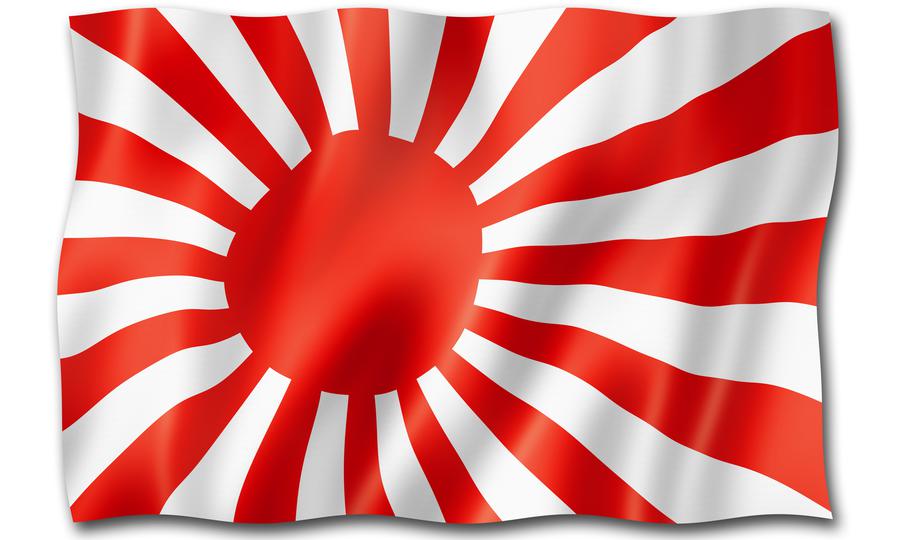

Young South Koreans are less inclined towards reconciliation with Japan than their parents. Photo: iStock

Taking up is hard to do – but when it comes to national reconciliation after war and atrocities, it is the generation that actually experienced the horrors that is likelier to forgive and reconcile than succeeding generations, indicating that current animosities between Seoul and Tokyo will not improve soon, if ever. Andrew Salmon specially for the Asia Times.

“People who have undergone suffering are the first to try and move toward reconciliation,” said Volker Stanzel, vice-president of the German Council on Foreign Relations, adding that there also needed to be visionary and pragmatic leadership. “We need people on both sides who are courageous enough to say, ‘We are ready to move on,’” he said.

These factors are particularly critical given that national memory is “fluid” and “can be manipulated,” Stanzel added.

Pragmatic leadership

Stanzel was speaking at a panel discussion titled “Collective Memory or Collective Future?” at the Asan Plenum, an international conference held in Seoul last week by the Asan Institute, a Seoul-based, conservative think tank.

He cited as a standout example the Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, who approached the conservative West German Chancellor Konrad Adenaur in New York in 1960 – only 15 years after the Holocaust – to kick-start reconciliation between Tel Aviv and Bonn.

Other examples include the accord signed between Israeli President Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in 1978, after multiple wars between the two states, and the moves by white South African President FW De Klerk and the black African National Congress leader Nelson Mandela to dismantle apartheid in the early 1990s.

It is critical that the issue is not left to succeeding generations – who will become imbued with collective memory.

“Those who believe that time will calm the waters and resolve the issues are wrong,” added David Harris, of the Jewish American Committee. “They will not.”

He cited as an example the continued anger among Armenians and parts of the international community at Turkey’s ongoing refusal to recognize or take responsibility for the Armenian genocide of 1915-1917. Some historical grievances – such as Serbia’s ongoing sense of victimhood related to its defeat by the Ottomans at the Battle of Kosovo – even date back to the Middle Ages.

In East Asia, more than seven decades have passed since Japan’s 1945 defeat. But for the above reasons, it looks unlikely that South Korea and Japan – the two leading democracies and US allies in Northeast Asia – can overcome their historical differences.

Reconciliation overturned

“Collective memory directly informs our foreign policy,” said South Korean Hahm Chai-bong, the head of the Asan Institute. “History is extremely politicized.”

The two ideological pillars on which South Korea was built in the 1950s were, he said, anti-communism and anti-Japanese nationalism. “At the height of the Cold War, that worked quite well,” Hahm explained. “Once the Cold War ended … one of the original identities of the [South] Korean people had gone.”

It was at the apex of the Cold War that Seoul-Tokyo reconciliation took place. In 1965, the two capitals normalized diplomatic relations and Japan paid US$800 million in soft loans and reparations – money that formed the startup capital for Korea’s “economic miracle.”

But there were complicating factors. South Korea’s then-President Park Chung-hee was an authoritarian leader who had seized power in a coup and who had served in the Japanese Army in his youth. Today, he is reviled by many South Koreans – particularly the young.

“South Koreans see [the 1965 diplomatic normalization] not as the pragmatism of overcoming history, but of a collaborator going against nationalist sentiment,” said Hahm. “Park said, ‘Nationalism be damned, we have to build up our economy!’ It was an enlightened decision, but from the nationalist point of view, it is excoriated.”

The centrality of anti-Japaneseism may explain why modern South Koreans make no emotive calls for apologies from North Korea – which sparked the Korean War, a three-year conflict which wrought more destruction and killed more Koreans than 35 years of Japanese colonialism – or from China – which ensured the continued division of the peninsula when it intervened to save a collapsing North during the Korean War.

“It is a very selective collective memory,” Hahm said.

With the generation who actually experienced colonialism fading away, there are no players on the political scene who seem interested in overturning or even questioning current sentiment.

The failure of apologies

A further issue is degree of victimhood. “The greater the suffering, the greater the opportunity for reconciliation,” Stanzel explained.

In Korea, some Japanese policies were clearly atrocious, including the brutal suppression of a 1919 independence movement, the recruitment of girls as “comfort women” for military brothels and even stipulations that Koreans adopt Japanese names.

However, colonial Korea did not suffer the mass killing and destruction that took place during Japan’s invasion of China, nor the genocide that marked Nazi policy toward Jews.

Moreover, among ex-colonial powers, Japan is a model apologist. It has offered scores of apologies over the years, by persons including emperors, cabinet secretaries and current conservative Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Former prime minister Junichiro Koizumi even made a bow of atonement at Seoul’s Seodaemun Prison, where Korean independence activists were imprisoned and tortured by colonial authorities.

Yet relations have steadily worsened in recent decades. Many Koreans argue Tokyo’s reparations and contrition are undercut by repeated visits by Japanese politicians to the controversial Yasukuni Shrine, and by textbooks which do not adequately address Japanese atrocities.

Media and interest groups rejected a Japanese public-private compensation fund that some comfort women received and slammed a 2015 bilateral agreement, that the majority of living comfort women accepted, on the grounds that the related apology delivered by Abe was insincere.

The current Moon Jae-in administration has ceased to abide by the terms of the 2015 agreement and has also overseen judicial moves to demand compensation from Japan on forced labor – something Tokyo insists was dealt with in the 1965 national compensation package.

All this leaves Seoul as Asia’s most persistent and vocal critique of Japanese historical aggression.

“Probably, all other countries have reconciled with Japan,” noted Stanzel, who formerly served as Germany’s ambassador to Tokyo. Hahm recalled his surprise to note the lack of animosity toward the former colonial power when he was a student in Taiwan. “I thought all Asians hated Japan, like us!” he said.

Last year, Philippine officials removed the statue of a comfort woman placed in Manila by NGOS, saying there was no need to inflame relations with Japan over an issue that had been “settled.”

Last month, a Japanese naval vessel attended a Chinese naval review flying its “rising sun” naval ensign. South Korea, however, has refused in recent years to permit Japanese ships to attend reviews if its ships fly the ensign, a move some criticize as “extreme.”

Even so, Hahm held out a ray of hope, noting that on the personal level, South Koreans are pro-Japanese culture. He cited the record seven million South Korean tourists who visited Japan last year and the current craze for Japanese food and izakaya-style pubs among youth.