[Analytics] Kishida’s new capitalism raises more questions than it answers

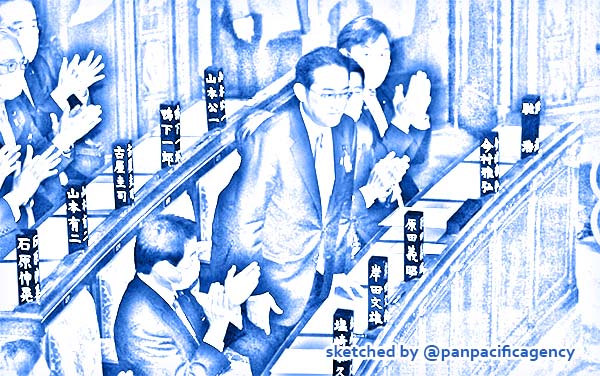

Fumio Kishida, center, bows after being named the new prime minister of Japan at a plenary session of the House of Representatives on Oct. 4, 2021. (Mainichi/Yuki Miyatake). Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s new economic program is gradually taking shape via a series of major policy announcements and record-breaking government spending initiatives. Aurelia George Mulgan specially for the East Asia Forum.

These include ‘an economic stimulus package that dwarfs anything announced by his predecessors’, the biggest supplementary budget in history amounting to 36 trillion yen (US$314 billion) for fiscal year 2021, a national budget plan allocating 107 trillion yen (US$933 billion) for fiscal year 2022 and a fiscal year 2022 tax reform plan.

The stated mission of the government is to deliver economic measures that will ‘overcome COVID-19 and pioneer a new era’ including ‘the realization of a new form of capitalism, the linchpin for reviving the Japanese economy’. For Kishida, ‘new capitalism’ represents a necessary economic model upgrade where ‘rather than leaving everything to markets and competition … public and private sector entities together play their roles’.

Promoted through public–private partnership, this ‘new form of capitalism’ is intended lead to faster economic growth and higher wages. Kishida’s ‘new capitalism’ rejects neoliberalism predicated on market dominance, which he holds responsible for promoting greater inequality and poverty, as well as for exacerbating climate change.

Kishida wants to distribute the fruits of economic growth more directly to lower and middle-income groups through redistributive policies rather than rely on the ‘trickle-down’ economics that characterised the Abe administration. ‘New capitalism’ embodies an implicit rejection of Abenomics in terms of both national economic strategy and policy sloganeering. Politically, this is a deliberate challenge to Abe’s legacy and appears to be a popular move with majority support among the Japanese public. Whether this rejection extends beyond rhetoric is questionable, however, particularly in areas such as massive fiscal stimulus, quantitative easing and policies that deliver wage increases.

Questions arise about how the range of spending and incentive programs will create a ‘new form of capitalism’. The connection between new capitalism, the targets for government assistance, and other proactive measures, needs careful clarification. Promoting new industries is not necessarily synonymous with establishing a new form of capitalism. Although Kishida has made clear his dedication to implementing his policy agenda, ‘new capitalism’ is fast turning into a label of convenience for a range of disparate government measures and spending initiatives.

In Kishida’s New Year’s speech, he nominated specific elements — digitalisation, climate change, economic security, innovation, and science and technology — as ‘engines of growth’, reiterating the importance of tackling disparities, bringing about redistribution through wage increases initiated by companies, and greater investment in people. But the respective roles of these factors in establishing a ‘new form of capitalism’ still needs elaboration. Whether private corporations will fall into line with Kishida’s wishes also remains an open question.

Kishida’s economic program has been heavy on rhetoric but light on reform. The overarching goals set for his administration incorporate variants of the phrase ‘growth and distribution’, including ‘creating a virtuous cycle of economic growth and wealth distribution’.

In practice, Kishida quickly reversed the order of his ‘virtuous cycle of growth and distribution’ to ‘distribution to spur growth.’ Distribution has clearly become the top priority — sourced primarily from government coffers in the form of a ‘cash splash’ and baramaki (government handouts) — rather than the fruits of economic growth or reform.

Implementing Kishida’s ‘new capitalism’ has thus entailed all gain and no pain at the public’s expense. It has become a convenient label for a traditional LDP-style big spending policy — albeit, for spending targets that focus on large social and economic groupings, and on strategically and socially important industries, rather than on traditional LDP special interests.

During his campaign for the LDP presidency, Kishida very quickly backed off the main policy instrument that would have provided a source of cash to be redistributed to employees and to lower and middle-income groups — taxing investment income by raising the capital gains tax, thus making corporate profits a source of economic growth.

Nor is Kishida seeking funds from sources such as corporate tax hikes which, if combined with increased financial income taxes, would have amounted to substantial tax reform. He has also failed to implement the introduction of a carbon tax levied in proportion to companies’ greenhouse gas emissions in line with new capitalism’s major goal of transitioning Japan to a carbon-free society.

These policy backdowns have disappointed expectations given that economic reform was touted as the most urgent item on Prime Minister Kishida’s policy schedule. Yet being in pre-election mode means that Kishida is under pressure to come up with policies that deliver economic and financial benefits quickly and directly to Japanese voters. Economic reform has, so far, taken a back seat to Kishida’s spending, a commitment he can justify in terms of invigorating the Japanese economy suffering from COVID-19 fallout.

In pushing Japan’s fiscal debt beyond an unprecedented one quadrillion yen (US$10.5 trillion) in outstanding government bonds, Kishida has prioritised the political rationale for ‘big spending’ — promoting economic measures that maximise the benefits to as many voters as possible, ensuring the consolidation of his leadership and the LDP’s success in the July general election.

The ‘big spend’ is coming first because of the electoral timetable and the convenient rationale that the COVID-19 economy needs boosting. But if Kishida were serious about the necessary economic reforms to create his ‘virtuous cycle of growth and redistribution’, he would implement policies with far greater potential to boost economic growth such as adopting measures to raise real wages and productivity, and completing the structural reforms promised but not delivered by Abenomics.

Clearly Kishida’s ‘new capitalism’ remains a work in progress. Perhaps realising the ideals and objectives of his newly announced ‘grand design’ of ‘new capitalism’, and implementing his summer action plan for ‘new capitalism’, will provide the answers.

Aurelia George Mulgan is Professor at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, the University of New South Wales, Canberra.