[Analytics] Japan and Australia step up defence cooperation

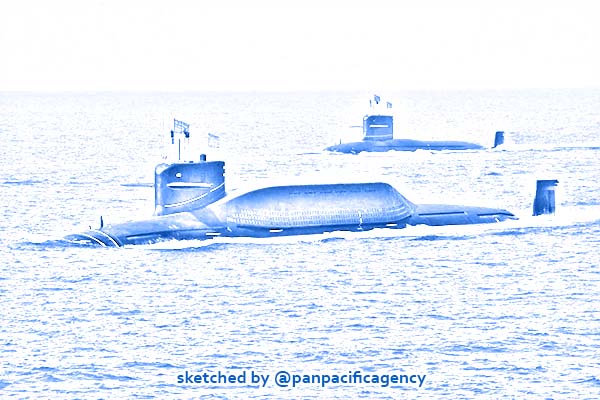

Two upgraded Type 094A nuclear submarines have gone into service in China. Photo: Reuters. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

The Japan–Australia Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) was finally signed on 6 January 2022. Under the increasingly severe strategic environment in the Indo-Pacific region, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida described it as a ‘breakthrough’, and Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison called it a ‘landmark treaty’. Kei Koga specially for the East Asia Forum.

The RAA is pivotal for further strategic cooperation between Japan and Australia, and contains significant strategic potential for furthering Indo-Pacific minilateralism.

The RAA enables Japan and Australia to enhance their power projection capabilities. But this agreement will not drastically strengthen their respective military capabilities. Japan and Australia do not possess the military assets to sustain a long-term overseas deployment. Japan also has additional hurdles, such as the Article 9 ‘peace clause’ of its post-war constitution, which prohibits it from possessing offensive weapons. By facilitating logistic procedures through the RAA, Japan and Australia are likely to focus on bilateral cooperation, such as humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, and joint military training exercises in the region.

This logistical process can help to maximise the potential of Japan–Australia military cooperation by increasing operational efficiency. The new agreement creates a strategic advantage for Japan and Australia to access the Southwest Pacific, the Indian Ocean and Northeast Asia. The enhancement of interoperability and access is vital for timely power projection, particularly in times of regional instability, including cases such as the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea.

Such bilateral defence cooperation has been increasingly consolidated since the 2007 Japan–Australia Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation. In November 2021, the Japan Self-Defense Forces (SDF) applied the 2015 security bills, which permit limited forms of collective self-defence, to guard Australia’s military assets during a joint exercise. This was the first time for the SDF to conduct such an operation for a country other than the United States. Japan–Australia security relations are often described as a ‘quasi-alliance’ — this becomes even more so with the RAA.

The RAA has become a model for Japan’s strategic partners when strengthening military cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. This is particularly true for the United Kingdom. Japan and the United Kingdom already have strong security ties, which were strengthened under the second Shinzo Abe administration from 2013. The two countries have a 2+2 dialogue, concluded the Agreement on the Security of Information in 2014 and the Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement and Japan–UK Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation in 2017.

These Japan–UK defence agreements are identical to Japan–Australia ones. In fact, Japan and the United Kingdom begun bilateral negotiations for an RAA in October 2021. Given the United Kingdom’s ‘Indo-Pacific tilt’, Japan and the United Kingdom aim to conclude the agreement as early as possible. To this end, the Japan–Australia RAA has become a useful model.

The RAA also enables Japan to create a security linkage with AUKUS. Admittedly, the main priority of AUKUS is to enhance Australia’s military capabilities through its acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines, which significantly increases its power projection. It is highly unlikely that Japan would be eager to acquire such capabilities as its military capabilities are still constrained politically and constitutionally.

Yet while the focus of AUKUS is primarily on the development of military assets, the frequency of military exchanges — including joint military exercises and trainings — will likely increase. If such an opportunity arises, Japan is the strongest candidate to participate in joint defence activities.

AUKUS collaboration on defence capabilities and technologies ranges from cyber capabilities to artificial intelligence to quantum technologies — areas that Japan is also interested in.

Japan still faces obstacles in fully cooperating with AUKUS. But starting from a relatively easy entry point, such as cyber security cooperation, it is possible that Japan can observe AUKUS meetings such as through an ‘AUKUS Plus’ format.

Such a possibility is likely to be enhanced when Japan and Australia renew their Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation, and in doing so more closely align with AUKUS. This also opens a possibility to connect the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue with AUKUS as its agenda overlaps — such as on critical and emerging technology and cyber security.

These defence networks are useful for US allies to deter strategic encroachment when the US military commitment to the Indo-Pacific is considered to be weakened, as the Ukraine crisis currently indicates.

This type of defence cooperation aims to maintain the strategic balance in the region, and does not hinder the development of existing regional security frameworks, such as the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting. But regional states may express concerns about the potential for an arms race in the Indo-Pacific, as Indonesia and Malaysia did after AUKUS was established in September 2021. To alleviate such concerns, Japan, Australia and other like minded states need to maintain their defence postures while making them as transparent as possible to reassure regional states — particularly ASEAN members — about the objectives of those emerging frameworks.

Japan–Australia defence collaboration through the RAA has taken a small step toward stabilising the Indo-Pacific strategic environment. But the RAA has significant strategic implications for the future of the regional balance of power.

Kei Koga is Assistant Professor at the School of Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.