Foreign investments flow to neighbors instead of Indonesia: World Bank

Switzerland-based pollution mapping service AirVisual revealed that Jakarta had the world's worst air quality on Friday last week. It was listed as the world's second worst on Wednesday evening. (Antara Photo/Muhammad Adimaja). Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

JAKARTA, Sep 10, 2019, The Jakarta Post. Indonesia is struggling to attract foreign investments, which are instead going to neighboring countries such as Vietnam and Cambodia as they embark on deregulation and policy solutions, according to the World Bank, reported The Jakarta Post.

“Businesses are moving out of China but are not coming to Indonesia because Indonesia’s neighbors are more welcoming,” reads a slide from the World Bank presentation material conveyed to President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo last week, a copy of which was obtained by The Jakarta Post.

“Moving factories from China to Indonesia is risky, complicated and would take at least one year if not more, while the process is certain and much shorter in Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Taiwan.”

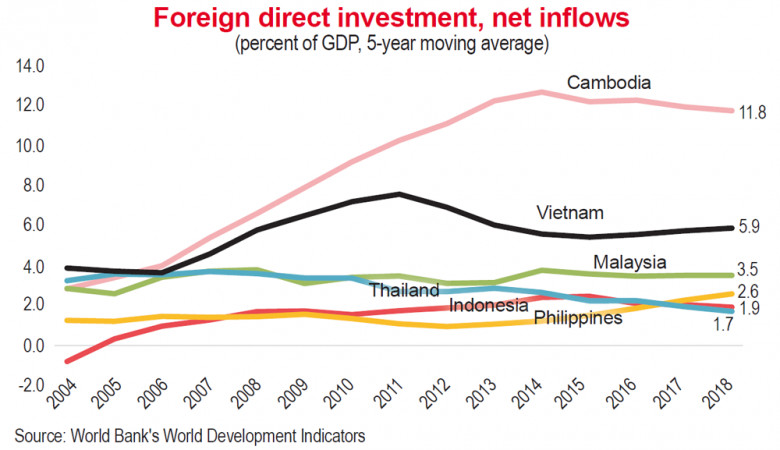

Indonesia’s net foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows only accounted for 1.9 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) last year, compared with 11.8 percent booked by Cambodia and 5.9 percent by Vietnam, the bank’s data show.

Between June and August 2019, 33 Chinese companies announced plans to set up or expand production abroad, of which 23 are going to Vietnam and the remaining 10 to Cambodia, India, Malaysia, Mexico, Serbia and Thailand, according to the World Bank.

The data highlighted Indonesia’s relative inability to capture one of the silver linings of the ongoing trade war between the United States and China, namely the possibility of factory relocation from the latter to circumvent tariffs imposed by the US on Chinese goods.

The Washington, DC-based lender highlighted lengthy procedures businesses must endure to operate in Indonesia as the primary reason for the lack of foreign direct investment coming to the country. Regulatory uncertainty and complex bureaucratic processes also made Indonesia less interesting than other neighboring countries.

“Ministers are making too many rules, and increasingly so,” the bank writes, highlighting more than 6,300 ministerial regulations issued from 2015 to 2018, representing 86 percent of central government laws and regulations. That compares with 5,000 regulations representing 82 percent of central government laws and regulations issued from 2011 to 2014.

The government is currently in the process of identifying all of its rules deemed to impede investors, which would be simplified or annulled in an omnibus law with the aim of attracting more investments, said the Office of the Coordinating Economic Minister’s deputy head for macroeconomics and finance, Iskandar Simorangkir.

Iskandar acknowledged that investment problems in Indonesia did not only relate to fiscal incentives, saying: “Indonesia has offered fiscal incentives but it’s not the only factor to attract FDI, which also relates to other factors such as land acquisition, infrastructure and simplification of the licensing process.”

Above all, Indonesia’s “allergy” to foreign investment needs to be addressed so the government can push for “bold” and “swift” policy reforms in attracting FDI and benefit from factory relocations from China, said Shinta Kamdani, the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (Kadin) deputy chairwoman.

The same “allergy” has discouraged foreign businesses from investing in Indonesia.

“The government also has to solve the problem of regulatory conflict between the government and regional administrations that has often been a problem for investors,” added Shinta.

The same sentiment was echoed by foreign business chambers in the country. American Chamber of Commerce in Indonesia (Amcham) managing director Lin Neumann told the Post that many American businesses in Indonesia had complained about the country’s complex and restrictive regulatory environment.

Neumann cited FDI restrictions on Indonesia’s Negative Investment List (DNI) as discouraging American investors from investing in Indonesia. “It sends a message to investors that they are not welcome,” he said over the phone.

British Chamber of Commerce in Indonesia (Britcham) executive director Chris Wren added a point that Britain-based businesses felt there were many overlapping regulations across a number of sectors and even administrations. Such a state of affairs, he said, created uncertainties that impacted businesses’ ability to manage risks.

Furthermore, Britcham cited other problems that made it harder for foreign businesses to come into the country: a short supply of properly skilled staff, dated labor laws and difficulties to obtain work permits for key expatriate staff.

In order to solve these problems, Wren suggested ministries develop good and open communication with stakeholders to be able to cater to their aspirations.

“We’re also calling for a much faster approach to encourage greater international influence at all levels of education to address the talent crisis,” he added.