[Analytics] Hong Kong’s ethnic minorities confront new national security law

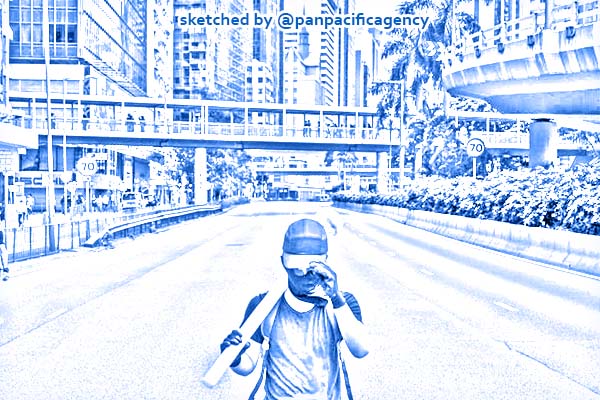

The decision comes as protests continue to rock Hong Kong. PHOTO: NYTIMES. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

Ethnic minorities in Hong Kong who often confront language and cultural barriers now face new challenges in the form of the national security law imposed July 1 by Beijing, which brings both uncertainty and a sense of the unknown. During the pro-democracy movement that rocked the city for months last year, many chose to remain mum. Some are now breaking that silence. Jay Ganglani specially for the Asia Sentinel.

As of October 2019, about a third of the ethnic minorities, who make up 8 percent of the city’s population, were South Asians. Many of them were born in Hong Kong, including Jeffrey Andrews, the first social worker to ever come from an ethnic minority.

Despite now being the poster boy for ethnic minorities, Andrews had a tumultuous youth that saw him join a triad group at the age of 16. Two years later, he found himself behind bars for assault and stealing a mobile phone, but was saved by a social worker who saw his potential to become a leader.

The national security law, which has been the topic of concerned conversation since it came into effect on July 1, is regarded as only the latest example of Beijing’s tightening control over freedoms following more than a year of social unrest. It is aimed at preventing and punishing acts that are deemed by the central government as endangering national security.

Andrews, who also became the city’s first pro-democracy ethnic minority candidate to run during the recently concluded Hong Kong primary election in July, believes that Indian Hong Kong residents could be targeted amid recent rising tensions between India and China.

“What happens if you’re celebrating India’s Independence Day tomorrow and you’re waving an Indian flag, would that now be deemed as a national security threat?” he asked.

The uncertainty and lack of clarity surrounding what the law actually entails, he says, remains scary because only government officials know what may constitute endangering national security given the lack of action in explaining it. Andrews maintained his faith in the one country, two systems principle agreed between China and the UK prior to the 1997 handover to China and the city’s rule of law when asked about whether he was afraid of what the future may hold for ethnic minorities.

“For the long term, I believe in the Hong Kong people and our core values,” he said.

Hong Kong’s ethnic minorities include Filipinos, Indonesians and Caucasians, in addition to the South Asians either living or working in the city. According to a study conducted by Associate Professor Puja Kapai from the University of Hong Kong’s Faculty of Law in concert with the Zubin Foundation, which interviewed more than 250 ethnic minorities between the ages of 16 and 24, only 7 percent said they liked being identified as minorities.

One such student who took part in that survey and asked to remain anonymous over fears of being targeted under the national security law is a Hong Kong Pakistani in her final year at the University of Hong Kong. She is concerned about what the law could mean for her as a Muslim living in the city.

“While I still do have some faith in Hong Kong, I also did not see the national security law coming if you asked me five years ago, for instance,” she said. “To add to all of this, the troubling situation in Xinjiang with its crackdown on Uyghurs and Muslims is extremely worrying as mainland China’s national security law talks about preventing and resisting harmful culture.”

Of the 253 participants in the study, 64 percent were born in Hong Kong, with the vast majority members of low-income families.

“In the future, because we all have different religions, will ethnic minorities in Hong Kong be part of that same harmful culture? Everything is uncertain at the moment,” she added. With around 390,000 domestic helpers living and working in Hong Kong, some of whom consider Hong Kong as their home, they too have their apprehensions regarding the city’s future.

Two domestic helpers, one from Indonesia and another from the Philippines, both in their mid-40s, told Asia Sentinel that the law doesn’t appear affect their jobs, but they are concerned about what it may mean for the city’s freedoms.

Unlike Western nations, domestic workers are a common staple in Asia, including in major cities such as Hong Kong and Singapore, and particularly so among rich and affluent families.

“You hear rumors that WhatsApp and Facebook are going to be banned, so that makes me afraid,” said the Indonesian. The sense of the unknown, she said, makes her wary if she will continue to be able to communicate with her family back home in the weeks and months to come.

Meanwhile, a spokesperson from the Equal Opportunities Commission, the city’s statutory body that looks after issues of sexism racism, and disability, told Asia Sentinel that all Hong Kong citizens, including ethnic minorities, must abide by the national security law and that the law would have no bearing on the department’s work, as they are an independent body from the government.

Jay Ganglani is a Hong Kong-based undergraduate student and an Asia Sentinel intern.