[Analytics] China-Russia relationship model for major powers

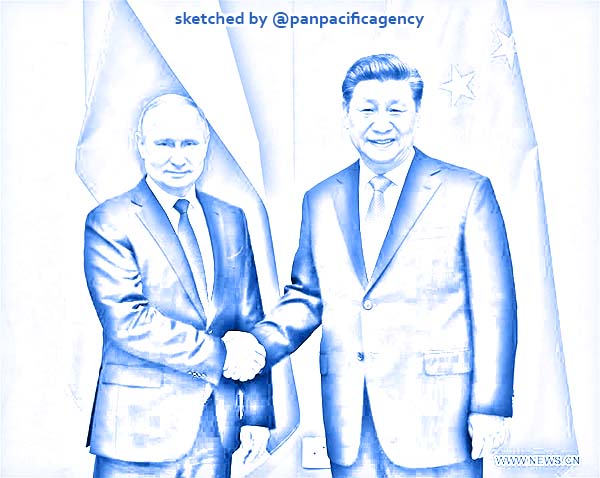

Chinese President Xi Jinping meets with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Brasilia, Brazil, Nov. 13, 2019. (Xinhua/Pang Xinglei). Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

For the foreseeable future, Russian-Chinese relations are likely to be closer, and more productive than Russian-American ones. This is not based on emotions, but on national interests. Dmitri Trenin specially for the Global Times.

The sudden deterioration of US-China relations to the level of confrontation is perhaps the most important geopolitical development that happened during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It appears that a point of no return has been reached. What started as a trade war and a conflict over intellectual property rights has morphed into an antagonism that encompasses the domestic politics of China (Hong Kong, Xinjiang, Tibet) and ideology (Washington has “discovered” that China is ruled by the Communist Party). It further involves geopolitics (from the South China Sea to the Belt and Road Initiative) and strategic issues. An active bipolarity between the world’s two most powerful countries is emerging again. This has major consequences for the global system.

All it took was President Donald Trump in the White House to debunk the decades-old US strategy of hedging against China while engaging it at the same time. This was replaced with a strategy to slow down China’s rise and shore up America’s primacy. It dawned on Trump that a continuation of former US policies would lead to China beating America at its own game of mastering economic, financial, and technological power, all backed by a powerful military. By the mid-2010s, it appeared that if unchecked, China would surge ahead and leave the US behind within a generation: a prospect impossible to contemplate for many Americans.

A quarter-century after the end of the Cold War, a major power rivalry again tops the US foreign policy agenda. President Trump not only declared China a strategic competitor, he went on to physically destroy the apparent symbiosis of a “Chimerica” that had mesmerized so many people on both sides of the Pacific just a dozen years ago.

Once again, an old maxim is proven right: close economic ties in the absence of a secure political alignment are not strong enough to prevent geopolitical competition. The fact that the US’ China policy is among very few issues where Trump and his Democratic foes are essentially on the same side testifies to a consensus within the American political class that is unlikely to unravel. Whoever wins the US presidential elections in November will most probably stay the course. The style will change if it is Joe Biden, but the substance will not.

This all came as a shock to the Chinese whose strategy for their country’s continued rise was set within a system still dominated by the US. China used all the advantages that system had to offer and decidedly shunned confrontation. Beijing is ever ready to make tactical concessions on the way to its long-term strategic objective. But Washington has changed the game completely. As a result, China’s policy will have to be reassessed, so that a new strategy can be developed to deal with the reality of confrontation. This is a challenge to China’s leadership, pushing it toward becoming a global geopolitical actor, not just a geoeconomic one.

The coming bipolarity will not necessarily be bloc-based like the 20th century’s US-Soviet one. Many US allies around the world – Europeans, above all – value their economic links to China and fear no military threat from Beijing. They will want to wish to keep the US protection that they had become used or addicted to. But they will likely balk at US-imposed restrictions on trade and technology issues. Even countries that have difficult relations with China and partner with the US, such as India and Vietnam, would want to stay geopolitically independent from Washington. China’s foreign policy needs to fully recognize that and draw practical conclusions.

Russia is China’s close partner. The relationship can be best described as an entente – a basic agreement between Moscow and Beijing on a host of issues. These range from a general worldview to respecting each party’s interests to active cooperation on a wide range of issues to friendly consultations, including on most sensitive subjects. The Sino-Russian relationship is based on a combination of reassurance and flexibility. Neither China nor Russia has reasons to fear a stab in the back. Both Russia and China are free to pursue their own national interests as they see fit. This is a model relationship between two major powers.

Washington will not be able to turn the US-China-Russia triangle to its favor, as it managed to do in the 1970s. As things stand now, there is simply nothing Washington can offer Moscow to turn it against Beijing. Of course, Russia is adamant about preserving its sovereignty and freedom of choice. It abhors becoming anyone’s junior partner. It abhors even more being drawn into other people’s fights. It has its own confrontation with the US to manage. Moscow seeks an equilibrium vis-à-vis the US-China conflict. Equilibrium, however, does not mean equidistance. For the foreseeable future, Russian-Chinese relations are likely to be closer, and more productive than Russian-American ones. This is not based on emotions, but on national interests.

The China-US confrontation will last a long while. In the end, the US will not defeat China. And China will not replace the US as the global hegemonic power either.

Dmitri Trenin, director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, has been with the center since its inception. He also chairs the research council and the Foreign and Security Policy Program.