[Analytics] Does Russia hold the key to China’s first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier

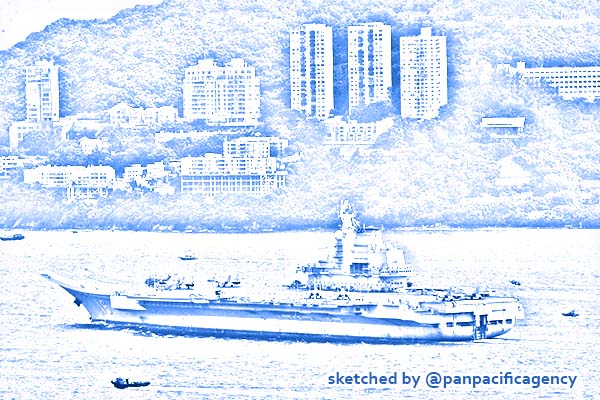

The Liaoning is China’s first aircraft carrier. Photo: Felix Wong. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

The former Soviet Union developed nuclear technology for its biggest ships by testing it on icebreakers. Now China is hoping it can do the same. Minnie Chan specially for the South China Morning Post.

China has invested heavily in the development of its aircraft carriers in recent years. Its first – the Liaoning – completed a major overhaul and upgrading programme in January, while its second – the home-grown Type 001A – is currently undergoing sea trials and could be ready to go into service by the end of the year.

A third carrier is also in development, though like its predecessors it will not be nuclear powered, and that, according to some, is where the problem lies.

Naval expert Li Jie said that to be truly competitive on the high seas, China’s military needed a ship capable of accommodating its J-15 fighters, and to do that took power, and lots of it.

“China really needs a more powerful, nuclear-powered aircraft carrier to catapult its superheavy carrier-based fighter jet, the J-15,” he said.

Although China already has nuclear submarines, the systems they use are unsuitable for carriers as they are not powerful enough.

France learned that lesson 25 years ago, Beijing-based military expert Zhou Chenming said.

“After seeing what happened with the [French carrier] Charles de Gaulle, China knows not to try and transfer nuclear reactors from a submarine to an aircraft carrier,” he said.

In a bid to cut costs in the development of the Charles de Gaulle – France’s first and only nuclear-powered carrier – its designers used two K15 submarine pressurised water reactors as the main propulsion system.

It did not work. The huge size of the vessel and the lack of power from the engines means it now has the unwanted title of being the world’s slowest carrier, with a top speed of just 27 knots. Experts say carriers need to be able to hit at least 30 knots to create the headwinds necessary to launch their aircraft.

“The combat capability of the Charles de Gaulle has been sharply reduced because of its low speed,” Zhou said. “It was a painful lesson for the French.”

To avoid that potential banana skin, China is now looking to a joint project with Russia.

In June last year, the state-owned China National Nuclear Corporation was invited by Moscow to bid for a nuclear-powered icebreaker project that will be powered by floating modular reactors.

The ship will be 152 metres (500 feet) long, 30 metres wide with a displacement of 30,000 tonnes.

The former Soviet Union started using icebreakers as experimental platforms for the development of nuclear reactors to power carriers in the 1950s.

By the time it was ready to start building its first nuclear carrier, the Ulyanovsk, in 1988, it had already built five nuclear icebreakers. Unfortunately, the carrier was never completed, as the USSR collapsed in 1991, four year before the its planned launch.

Li said that the benefit of testing systems on icebreakers was that they also demanded large amounts of power.

“The structural design of an icebreaker that allows it to cut through dense ice means it needs a strong propulsion system,” he said.

While China has good experience in the development of nuclear reactors for use on land, it has yet to master the “miniaturisation” process that is needed to make a nuclear power unit suitable for an aircraft carrier.

“China has strong naval building capabilities, but it is still very weak in nuclear miniaturisation. So it can learn from Russia,” Zhou said.

“Russia has the technology but no money, China has the money, but doesn’t have the technology. By working together China will move a step closer to one day launching a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier.”