[Analytics] Why China, like Japan, needn’t worry about paying all that debt back

Image by The Kathmandu Post / Shutterstock. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

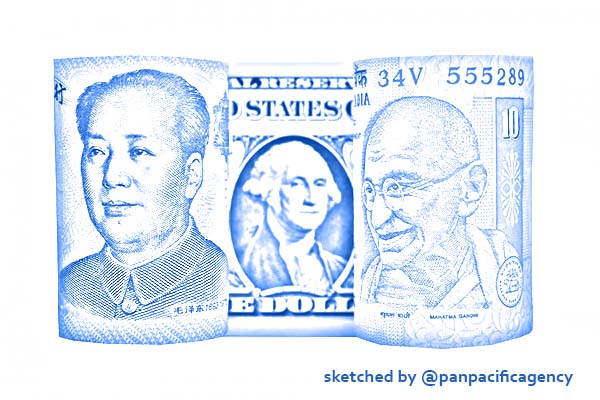

With China’s total debt hitting 317 per cent of GDP, it looks destined to join Japan, Greece and Italy on the OECD and IMF’s ‘wall of shame’. But why worry when Modern Monetary Theory suggests its debts may never need to be paid? Neil Newman specially for the South China Morning Post.

Major economies around the world are seeing their debt surge. For many years, Japan, Greece and Italy have topped the OECD and IMF’s “wall of shame”, and it appears they will soon be joined by China as the Institute of International Finance recently estimated China’s total debt hit 317 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) in the first quarter of this year.

GREECE IS THE WAY WE ARE FEELING

No one likes the thought of being in debt. After all, it must be paid back. And seeing one’s national debt compared with GDP is depressing and worrisome – just ask the Japanese who have been confronted with eye-watering numbers for decades. As debt rises, it is natural to wonder how the Chinese and the Japanese will ever manage to pay it back. Raise taxes? Sell more cars, electronics and plastic crap? Perhaps not. A novel way of looking at it, called Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), suggests they may never have to.

I’m not a trained economist, although I studied some theory when I arrived in the City of London in the early 1980s. My career has been based more on observation, learning “on the job” and drawing conclusions from what I thought was sensible rather than what it said in the book.

With that in mind, opening the OECD report on Japan, I am troubled at seeing the chart of gross debt to GDP in Japan plotted against Greece’s (page 16 in its 2019 report), which suggests there is a comparison to be made. That doesn’t sit right, as we know that Japan is rich and Greece is poor.

Gross numbers are lopsided, so perhaps net debt to GDP is the more relevant measure. After all, when we think of our own personal finances, we may have some savings, shares, property to weigh against our mortgage and credit-card bill. Looking at a company’s balance sheet, we are likely to take into account assets such as buildings, machinery and property as well as financial assets like cash, stocks and bonds. Yet still, on a net debt basis, the usual suspects appear at the top of the table: Japan, Greece, Italy, Portugal, etc. Something is amiss.

This prompted me to call the OECD office in Tokyo as I wanted to find out if they looked at Japan as a company balance sheet or a simple credit-card bill. Specifically, did they include assets held by the Bank of Japan (BOJ) in their calculations for net debt to GDP? It turned out that no, they do not. Therefore, their net debt-to-GDP ratios are wildly inaccurate.

SEPARATION OF CENTRAL BANKS AND GOVERNMENTS

The reason for not taking into account the BOJ’s assets is that there has to be a separation between governments and central banks so that you cannot offset assets of the BOJ against the government debt. It is simply not allowed, and for a good reason: to prevent the shenanigans that historically have led to hyperinflation. In times of extreme economic stress, central banks have uncontrollably printed money to keep the plates spinning – examples include Zimbabwe in 2007 and Yugoslavia in 1992.

To my mind, this one rule doesn’t necessarily fit all scenarios and it started a bee buzzing in my bonnet. Harare is not Tokyo, nor is Athens anything like Osaka. And certainly, the crumbling cities of Lisbon and Rome do not feel anything like Beijing or Shanghai. In my opinion, the main things to consider when assessing national debt, no matter how big the number, are: who actually owns the debt? And who expects to be paid back?

WHO OWNS THE DEBT?

One way to illustrate this is to consider the Newman household. Think of my dad as the government; generally, what he says goes. My mum is the bank; she issues the cash, has a few shares and keeps an eye on the premium bonds. My sister and I need to get a sub now and again and borrow some money, so dad asks mum to give us some cash. As long as there is no borrowing outside the family, the debt of the overall household does not change. As mum hands over the cash, we promise to pay dad back. At some point, in a moment of parental love, dad decides we don’t need to pay back the loan and tells mum to “rub it out”.

Scaling things up, this way of looking at it certainly applies to Japan, and probably China, as most of the debt is financed internally. Calculating the real net debt-to-GDP ratio for Japan is revealing, and it will be an interesting exercise to do for China at the end of this financial year.

WHAT IS JAPAN’S REAL DEBT?

The OECD economists in their 2019 report warn us that “Japan needs a detailed and concrete plan to ensure fiscal sustainability” as its government’s gross financial debt-to-GDP ratio is a shocking 223.4 per cent, and on a net basis is a nasty 126.9 per cent. They say Japan’s GDP in 2019 was 545 trillion yen (US$5 trillion). In its monthly newsletter, the Japanese Ministry of Finance states that the BOJ owns 43.2 per cent of all Japanese Government Bonds, about 486 trillion yen. If we knock that off the bill, Japan’s net debt-to-GDP ratio is 37.7 per cent.

Cynics will say the cost of financing the outstanding Japanese Government Bonds is a problem. But with interest rates low, the impact is reduced, and with only 7.1 per cent of Japanese Government Bonds held by foreigners, this amounts to the right Japanese pocket paying the left Japanese pocket.

As with any other central bank, the BOJ has assets, buying exchange-traded funds, real estate investment trusts, and has some stocks. The total amount of assets at the time of the OECD report amounted to about 85 trillion yen. Knock that off the debt, and the net debt-to-GDP ratio is 22 per cent. Following the logic of taking into account all of the assets, and debt, held domestically, we also need to include the 13.3 trillion yen of government debt held by Japanese households and 76.8 trillion yen in their pension accounts. Add that up and Japan actually has zero net debt – it is, in fact, a net creditor nation, like China.

CONVENTIONALITY BELONGS TO YESTERDAY

Extending the Newman household analogy, at some point in the future, perhaps when credit ratings agencies are voicing concerns again, the BOJ governor may give the prime minister a call and say, “Don’t worry, son, you don’t need to pay anything back, mum just rubbed it out.” The same logic would apply to other countries whose debt is largely owed domestically, if the economy is strong and its central bank can readily print money to ensure the country never defaults, according to MMT. Why worry about paying it back?

Neil Newman is a thematic portfolio strategist focused on pan-Asian equity markets