Political violence a threat to Myanmar’s election

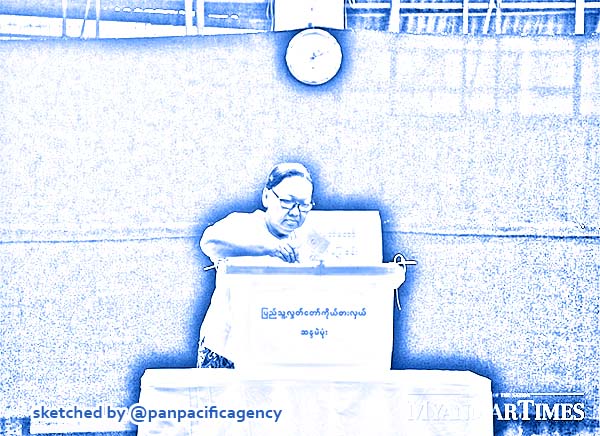

A woman casts her ballot during last year’s by-elections in Yangon. Nyan Zay Htet/The Myanmar Times. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

YANGON, Oct 16, 2020, Frontier Myanmar. Although elections in Myanmar since 2010 have been largely free of violence, there are worrying signs that tension could spill over during this year’s vote, including the post-election period, Frontier Myanmar reported.

The November 8 election is less than a month away. Campaigning got underway as soon as the Union Election Commission gave the all-clear in early September. Although there are some restrictions due to COVID-19 and campaigning is banned in virus-hit areas of the country like Yangon and Rakhine State, for the most part political parties have been in full election mode ever since.

The National League for Democracy swept the 2015 election. The huge margin of defeat was a rude awakening for the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party, along with many ethnic-based parties. Once they got over the shock, they took the 2015 loss as a lesson and started organising themselves for a tough fight in 2020.

Given the high stakes, the contest is going to be fierce. Fierce and robust contestation is generally the sign of a healthy election. It can draw out undecided voters and result in a better turn-out that more closely reflects the will of the public. But in a country like Myanmar, fierce contestation can also create a darker side – that is, the potential for violence. We have already seen a few examples of intense campaigning in several parts of the country. As someone who has been working on peace and conflict for decades, I am all too aware of the vulnerabilities that Myanmar faces in this regard.

When predicting the outcome of the election, many have forecast an outright win for the NLD or possibly some sort of coalition government. Few have considered violence as one of the potential outcomes from the vote.

Not everyone agrees with me, but I have argued repeatedly that there is an entrenched culture of violence in Myanmar. There is no more obvious time than an election for violence to show its ugly face. I am therefore deeply worried about the potential for violence before, during and after the election.

There are clearly reasons to be worried. There have been numerous and increasing instances of violence during the election campaign period. At first these incidents were not too serious – for example, party billboards being destroyed, defaced or vandalised – but the tone is getting more heated. We’ve seen hand grenades – thought to be duds – lobbed at the house of a local election official in the capital. USDP supporters have clashed with their counterparts from the NLD in numerous states and regions, including Mandalay, Magway and Ayeyarwady regions. In Shan State, the Restoration Council of Shan State has reportedly blocked a Ta’ang party from campaigning and been accused of kidnapping one of its members. Most recently, masked men abducted three candidates from the NLD in Taungup Township, in southern Rakhine State, on October 14.

We shouldn’t just be concerned about what happens on the physical campaign trail. This is an election campaign playing out on Facebook, and social media puts the huge divisions that exist in Myanmar – political, ethnic and religious – on full display. Fake news, unfounded accusations, name calling, personal attacks and other forms of abuse have become increasingly common among supporters of political parties. This dynamic can also reinforce the tensions happening out in the real world between rival supporters.

More worrying still are the predictions that this general election will generate more post-poll disputes than in previous years. If they are not resolved transparently and fairly, or the UEC’s decisions are perceived as biased, it will potentially lead to further violence.

Another critical element to consider is the country’s armed conflicts. Elections are being held in conflict-affected areas, including Rakhine State. There is a potential for a spike in clashes or violent acts during the election in these areas. Unlike before, weapons are now easily available in the cities in these areas. Areas of the country with a general history of violence are primed for further outbreaks during the election.

I am not aware of any election in Myanmar that has been completely violence-free, which is not surprising given Myanmar’s history of conflict. But I have been very proud that we have not seen serious or large-scale violence during our elections since 2010. We must strive to maintain this standard.

Leaders from both the NLD and the USDP have said that they are going to reign in their supporters following recent scuffles. In a VOA interview, they urged their supporters to campaign within the confines of the law. This is a good start but more needs to be done. Perhaps they should come up with a code of conduct for their supporters – certainly it seems that the UEC’s code of conduct is not enough.

I sincerely hope that I am overstating the risks, and that my assessment is incorrect. I would of course prefer to see a free, fair and clean election without violence, but we also should not ignore the risks that are clearly there. As members of the public, we should be vigilant to these risks, and do all we can to ensure violence does not break out or spread.