Bhutan’s target to become a 100 percent organic nation by 2020 delayed – pushed to 2035

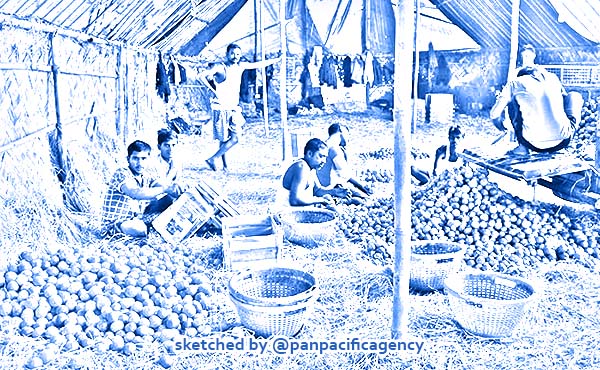

Mandarin exporters in Bhutan. Photo: Kuensel online. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

THIMPHU, Jan 5, 2020, Kuensel. In a bid to make agriculture more sustainable and to establish a resilient, productive organic farming system while preserving the environment, Bhutan set the ambitious goal of becoming the world’s first 100 percent organic nation by 2020, Daily Bhutan reported.

However, it has been four days since the 2020 deadline has passed. Yet Bhutan has only achieved about 10 percent of organic agriculture production, along with just about 545 hectares of crop land (less than 1 percent of its total arable land) being certified organic.

Till date, the country has only two internationally certified products – lemongrass and essential oil produced by Bio-Bhutan as well as 20 products certified by Bhutan’s local organic assurance system.

Currently, there are 24 farmer cooperatives, three organic retailers and one exporter involved in organic production and marketing in the country.

Since the establishment of the National Organic Programme (NOP) in 2008, the usage of synthetic fertilisers in Bhutan has remained stable.

However, the use of pesticides has been increasing with an average annual growth rate of 11.8 percent.

In order to become wholly organic, the country intended to phase out the use of harmful chemical fertilisers and pesticides.

Part of the 100 percent organic policy rationale was to promote Bhutan as an organic brand internationally, which would help commercialise small-holder agriculture, alleviate poverty, and add value to the tourism sector.

However, on a pragmatic level, achieving the target proved impractical, especially given the significant challenges involved.

This includes the fact that the country currently imports 45 to 50 percent of its domestic rice requirement from India and other countries.

Given the compulsions of ensuring food self-sufficiency and security and a desire to attain import substitution in agriculture, there has been a slow transition of Bhutanese agriculture towards an organic sustainable farming system since the 1960s, according to agriculture officials.

For the Ministry of Agriculture and Forests (MoAF), the priority and challenge is for Bhutan to meet national food self-sufficiency while keeping the agriculture systems largely organic.

A study in 2017 found that Bhutan’s organic crop yields on average to be 24 percent lower than conventional yields.

Looking back, experimental processes to promote organic farming in the Kingdom began in 2003, followed by institutionalised programs promoted to implement the National Framework for Organic Farming for Bhutan (NFOFB) in 2007 and the establishment of the NOP in 2008.

In addition, the ministry adopted an Organic Masterplan in 2012, backed up by a roadmap for Bhutan’s 12th plan, in which organic agriculture development strategies were laid out from 2018 to 2023.

Despite recognising the organic programme and giving it enough status to take up national organic agenda, the plan did not have adequate resources to meet the desired goals.

“The organic agriculture received relatively lower priority in the 11th Plan,” said an official.

Identifying the challenges

To compound matters, efforts to translate Bhutan’s organic vision into reality has met with different challenges.

Firstly, empirical data relating to organic agriculture is largely unavailable. The country’s attempt to encourage farmers to produce for the domestic and international market has so far only targeted single cash crops such as potato, hazelnut and cardamom.

Within the potato and rice farming communities, farmers had apparently been encouraged to significantly increase the usage of chemical fertilisers and pesticides over the last couple of years.

Secondly, the organic sector has been affected by a number of issues related to markets and value chains, including lack of appropriate supply-and-demand-side mechanisms such as the absence of price premiums as well as low consumer awareness.

Organic producers who gathered at a regional symposium on organic agriculture in Paro last month also mentioned that promoting and marketing organic products has been difficult.

Dawa Tshering, the producer of Organic Moringa Oleifere Tea, based at the Start up Centre in Thimphu, said that one of the biggest challenges confronting organic entrepreneurs was inadequate consumer awareness in the domestic market.

“Even when the products were sold at reasonable prices, many consumers prefer imported products,” he added.

Another challenge, he said was insufficient technical and financial services, on top of poor policy support.

Another organic producer, Kamal Pradhan, who manufactures organic fertiliser, vermin compost and chicken manure at Bhu Org Farm in the district of Gelephu revealed that some farmers are actually using chemical fertilisers to increase the yield.

When it comes to organic products, people usually associate them with higher prices.

“They are not aware of the enriched composting and beneficial micronutrients present in the fertiliser.”

For Pema Gyalpo, the producer of organic cleaning and bathing products, insufficient raw materials and the absence of advanced technology are the main problems which he face.

“There is enough demand for my products, particularly from the tourism service sectors, but unavailability of raw materials for all season hinders production,” he explained.

To address these issues, Pema Gyalpo is currently planning to expand the plantation of Loofa plants and looking into high-tech technology to scale-up his production.

The government has also stepped in to help organic entrepreneurs in capacity development and skills enhancement by providing trainings and networking platforms.

By prioritising the National Organic Flagship Programme (NOFP) for the development of Bhutan’s organic sector in the current Plan, organic producers remain hopeful that the demand for the region’s organic products in both national and international markets would grow further.

The National Organic Flagship Programme (NOFP) aims to improve the integration of the agriculture sector with its sub-sectors of livestock and forestry.

Programme Manager of NOFP, Kezang Tshomo said that the organic programme is expected to encourage organic production and value chain development.

This will potentially enable the marketing of organic certified products.

“The government will also support linkages related to market and organic inputs in addition to cost sharing support for farm equipment, infrastructure such as compost shed, and processing equipment, among others,” she added.

Thus far, the only district to become fully organic in Bhutan since 2004 is Gasa dzongkhag. The country now targets to achieve its 100 percent organic status by 2035.

By Chimi Dema. This article first appeared in Kuensel and has been edited for Daily Bhutan.