India’s sugar factories continue to let down cane growers

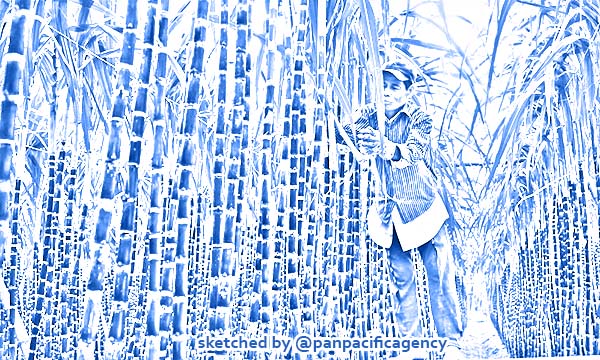

A man works on a sugarcane farm in Thua-Thien Hue Province. Photo by Shutterstock/Saigon85. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

NEW DELHI, Sep 20, 2020, The Hindu. During bifurcation, there were 29 factories in Andhra Pradesh, which came down to twelve last year. With sugar factories landing in trouble one after the other, there is no place that the cane growers can go. Chittoor district, considered the sugar bowl of Rayalaseema, is in dire straits, The Hindu reported.

During bifurcation, there were 29 factories in Andhra Pradesh, which came down to twelve last year. Of the six factories in Chittoor district, The Chittoor Sugars and Sri Venkateswara Sugars near Tirupati, both in cooperative sector, became non-functional long back. Of the four private factories, the ones at Buchinaidu Kandriga and Punganur had declared lockout.

The Sri Rangaraja Puram factory is doing fairly well, while the plant at Nindra, which is under tremendous financial pressure, has narrowly escaped auction of its machinery by getting an interim court order this week.

The government had scheduled the auction for September 10, but the factory had sought more time and finally secured an interim court order. “We will wait for the final order and proceed with the auction process by getting the stay vacated”, Assistant Cane Commissioner M. John Victor told The Hindu. Farmers who supplied cane to Buchinaidu Kandriga and Nindra factories have to receive ₹30 crore and ₹37.6 crore respectively.

“The first one declared lockout last year and its properties are being auctioned, but the latter one is resisting such an attempt”, observes Avula Srinivas Yadav, General Secretary of the Cane Growers Association (Nindra Zone).

A study of the cane sector shows that neither the farmers, nor the factories are happy with the output. Monsoon vagaries apart, the major problems plaguing the industry are the perennial pendancy in settlement of dues and plummeting of sugar price in the open market over the last decade. This led to a drastic shrinkage in cane area, with most farmers looking for ‘lucrative’ and less risky crops. “I have stopped growing cane a decade back as it was no longer remunerative. The malaise runs deeper in cane”, opines Mangati Gopal Reddy, state President of Federation of Farmers’ Associations (FFA).

The farmers incur huge cost towards labour for harvesting. With local workers lacking the expertise, the cane growers invariably depend on importing workforce that comes at a premium. A farmer spends anything between ₹750 and ₹1200 per tonne on labour, which should be curtailed to ₹500. Moving towards farm mechanisation, smaller harvesters are the need of the hour, as larger ones in the market are unable to manoeuvre the mostly small landholdings in this region.

Similarly, the factories can explore ancillary units to make ethanol and by products to shore up revenues. However, it may be recalled that the co-generation units ambitiously set up over the last decade had eaten away precious resources, instead of contributing to the factories’ profit.