[Analytics] Exporting China’s social compliance system

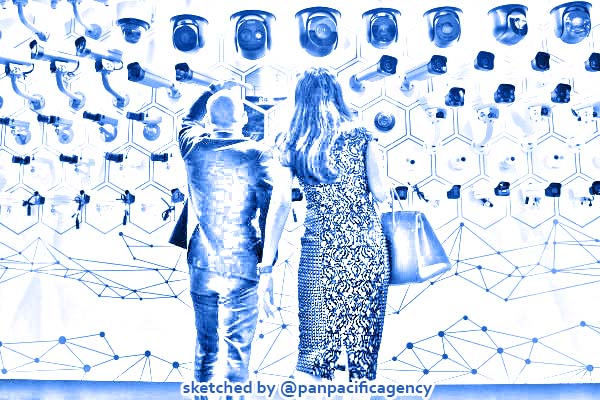

People look at surveillance cameras at the annual Huawei Connect event in Shanghai, China, 18 September 2019 (Photo: Reuters/Aly Song). Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

In the Middle Kingdom, privacy and individual good appear subordinate to all-purpose trust and collective good. This way of conceptualising things, along with modern technology and the advent of the digital world, helps the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to manoeuvre widely and implement new surveillance mechanisms. Vincent Boucher specially for the East Asia Forum.

New mechanisms are often subtler and less intrusive than the CCP’s traditional initiatives. The CCP’s traditional mechanisms included ‘struggle sessions’, organised violence, direct intrusion into private lives and institutions, a culture of denunciation and the use and perpetuation of China-as-victim narratives on screen and in diplomatic affairs. All of these have at least partially been replaced today by more modern means.

The CCP is now introducing new mechanisms, such as the Social Credit Score system (SCS) and the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP), as trust-promoting measures, implying that a sacrifice of personal information has become a necessity. From a realist perspective, Chinese President Xi Jinping and the CCP are strongly betting on increased returns — domestically and internationally — from the development, use and export of such mechanisms.

As the world order shifts, the CCP has doubled down on authoritarian surveillance and social control mechanisms. It is offering unaligned and developing nations alike an alternative to the current liberal democratic solutions offered by the West — an alternative that is different conceptually, materially and ideologically.

The CCP is mobilising its considerable resources to design and proliferate innovative social control mechanisms, inspired by traditional Maoist methods and bolstered by modern technology. Although under perpetual development, these strict and elaborate mechanisms have to a degree, sometimes at the cost of individual freedoms, generated intended results. As a result of some of its methods, the CCP further claims to be curbing the ‘three evils’: terrorism, separatism and religious extremism.

Chinese authorities capitalised on the 2008 Beijing Olympics to showcase their technical expertise in compliance mechanisms to foreign regimes. In a global environment characterised by increased interconnectedness and a shifting world order, these solutions were (and are still) presented as inventive alternatives to the perceived growing inefficiencies of Western liberal and democratic ideologies.

The CCP, in close association with Chinese high-tech firms, has since been contributing to the social compliance and surveillance apparatus of an increasing number of countries. Their reach is a testament to their flexibility in providing on a case-by-case basis free, partly free or paid telecommunications infrastructure, artificial intelligence (AI) surveillance and various forms of technical training.

The CCP has been successful in its dissemination of technology, with customers including Venezuela, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Mongolia, Zimbabwe, Malaysia and Brazil.

Venezuela received the means to develop its ‘fatherland card’ — a smart identification card with the potential to track economic, social and political behaviours. Ecuador acquired surveillance know-how and equipment. The Ethiopian government received telecommunications equipment and the means to control and monitor its usage. Mongolia was provided with security material, smart cameras and AI. Zimbabwe received facial recognition and surveillance technology as well as social compliance know-how. Malaysia gained high-tech policing equipment. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration stated it would introduce a bill to ‘make it compulsory to install facial recognition cameras in all public places’.

Beijing’s desire to position itself as a tech leader is transparent. It invests heavily in its tech sector, in tech infrastructure and in events such as the 2019 Global Digital Summit held in Xiamen. As Chinese companies build the technological infrastructure of the 21st century and provide training to their international clients and counterparts, the CCP’s promise is twofold. It promises foreign governments prosperity through cooperation and its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and stability through the proliferation and use of its population compliance mechanisms.

In an effort to proliferate the use and prevalence of authoritarian methods of social compliance, the CCP simultaneously pulls customers in and pushes its agenda out through economic and diplomatic streams. It pulls in states by showcasing its technology and attesting to positive results. The promises of stability, access to advanced technology and regime security effectively attract interested (mostly authoritarian) governments. Beijing also promotes its agenda downstream, presenting advantageous agreements to targeted states that are ideologically aligned, vital to the BRI or strategic geopolitical actors.

The export and international proliferation of authoritarian methods of social compliance could contribute to their acceptance, which raises important considerations. Democracies and their people must ponder the possible stability trade-offs associated with such mechanisms, nationally and regionally.

More precisely, it is not clear whether the presumed (or promised) gains in efficiency and stability, short- and long-term, counterbalance the reduction in individual liberties that might follow, especially given current human rights definitions. Governments should consider the implications of the widespread adoption of modern social compliance mechanisms domestically and internationally and adjust their policies to mirror their potential consequences.

Vincent Boucher is a conflict studies major at the University of Ottawa.