[Analytics] Managing Asia’s coronavirus response

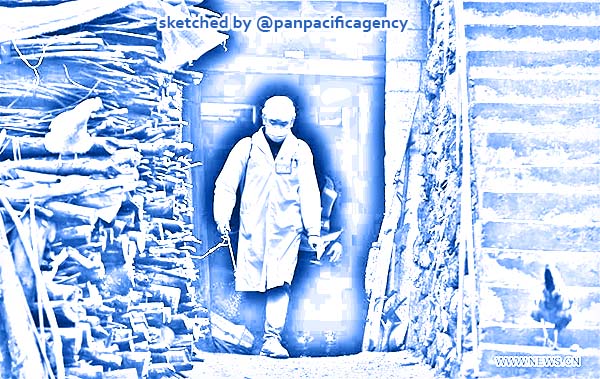

A medical staff disinfects houses in Dangjiu village in Rongshui Miao autonomous county, South China's Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, Feb 4, 2020. Various measures are taken across China to combat the novel coronavirus. [Photo/Xinhua]. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

The novel coronavirus (COVID19) has so far been reported in 24 countries and territories outside mainland China, where the outbreak was first reported last December. Measures have been taken to contain the spread of the virus but some at the cost of impeding regional connectivity. To better prepare for future outbreaks, it is necessary to build channels of trust, communication and information-sharing in peacetime, and increased investment in equitable health systems to support outbreak containment measures. Sara E Davies specially for the East Asia Forum.

Cases have been reported all across Asia. Indonesia, the most populous country of Southeast Asia, tested a suspected 38 cases that all turned out negative. But this month, Indonesia, along with a number of other countries that usually have strong travel and trade relations with China, announced a precautionary travel and trade ban.

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), said that the containment of COVID19 requires a policy trifecta. First, countries should share surveillance information, and if they cannot test for coronavirus then the WHO will facilitate sending samples to countries that can. Second, governments must work to contain the outbreak without trade and travel bans, which can affect information sharing. Finally, he stressed the importance of managing the information flow to people affected by the outbreak.

The ‘infodemic’ — social media rumours fuelled by false information — is harmful from a public health approach and xenophobic from a human rights perspective. Official government information is unable to keep pace with the spread of misinformation online.

There are three important messages that can be learned from this outbreak that are particularly relevant for Asia.

First, the peacetime coordination of the WHO’s International Health Regulations (IHR) needs ongoing financial and political support. Current debate is focussed on whether the IHR should be revised. The WHO could have declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) sooner to avoid countries taking trade and travel measures into their own hands. A ‘traffic light’ system could be used to help control panic when transitioning to a PHEIC. Perhaps there is also a need for an IHR emergency committee always on standby. If states adopt trade and travel bans in breach of WHO recommendations, then the declaration of a PHEIC and the IHR are rendered futile.

But revising a legal instrument that relies on the cooperation of even some of the most reluctant observers of international law in other domains such as human rights is not a convincing solution.

The big gap in the current IHR is peacetime coordination and diplomacy, ensuring that regions are ready to communicate during emergencies. In the past five years, much work has been dedicated to evaluating IHR compliance.

Ensuring that states have strong health systems is important but the WHO Joint External Evaluation (JEE) reports do not (and cannot) provide the diplomatic insight to determine whether to declare a PHEIC, and whether declaring a PHEIC can deliver the international cooperation required. The JEE reports could serve as a pathway to more effort in peacetime diplomacy — investing in channels of trust, communication and information sharing among states outside of the crisis. Information flow in Asia this time has been good because the Southeast Asian and Western Pacific divisions of the WHO have dedicated a lot of effort to achieving this.

Second, trade and travel bans potentially violate human rights, erode collective diplomacy and affect economic outcomes, disproportionately harming the economically vulnerable. Bans persist because people are frightened, and governments — democratic or not — cannot ignore people’s fear.

Further, civil society organisations are permitted to report outbreaks directly to the WHO under the IHR. But there is no evidence that they — along with social media and traditional media platforms, volunteer health workers and non-government organisations — are being incorporated into the IHR response. The politics involving countries that are prohibited from accessing Google and other websites may play a part. As a follow up from the JEE reporting process, the WHO could start having conversations with states about permitting more diverse domestic groups to be part of the discussion now or face more ‘infodemics’ at their peril.

Finally, there is the issue of funding for better understanding COVID19 and preparing for potential future outbreaks. The impulse to invest in rapid response units, vaccines and laboratories — provided investment is located in low and middle income countries — may help build regional capacity for technology transfer (vaccine production and supply).

It is also important to invest in equitable health systems. There was an injection of donor cash into Asia after the outbreaks of SARS and H5N1 avian influenza. This boosted influenza preparedness, epidemiological training, testing and local healthcare programs and resources. Investment created momentum and countries in the region have continued to invest in healthcare, generating some positive stories. Implementation is never perfect but such investments improve the capacity to detect, communicate and contain the spread of viruses during outbreaks. All investments can and should sit within a bigger picture of achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goal 3 of ‘ensuring healthy lives and promoting wellbeing for all at all ages’.

Sara E Davies is Professor and Australian Research Council Future Fellow at the Centre for Governance and Public Policy and Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University.