[Analytics] China’s leader attacks his greatest threat

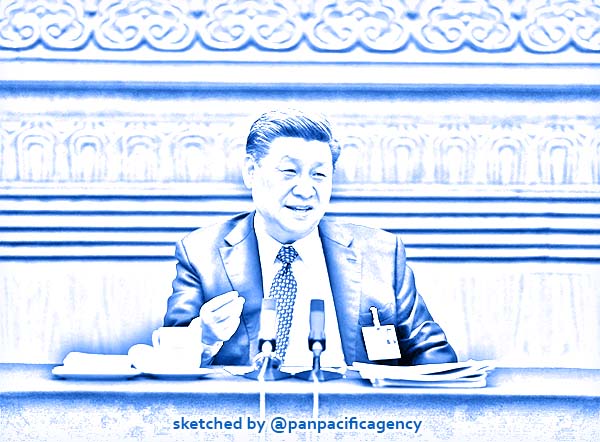

President Xi Jinping participates in a discussion with National People's Congress deputies from Hubei province on May 24, 2020 in Beijing. [Photo/Xinhua]. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

On March 11, 2007, Xi Jinping, then the top Communist Party official in Zhejiang province, near Shanghai, had dinner with the U.S. ambassador to China. The meal was part of the embassy’s outreach to up-and-coming Chinese officials. Xi, 53, was reputed to be among three officials in the running to replace Hu Jintao, China’s dour-faced leader. John Pomfret specially for The Atlantic.

Ambassador Clark T. “Sandy” Randt, a classmate of President George W. Bush, was impressed with Xi. In a cable recounting the dinner, Randt described the discussion as “frank and friendly.” Xi, as he always did with Americans, had lauded Hollywood movies and, fittingly for the party boss from a province that was a hotbed of entrepreneurial energy, praised a new law that would protect private investors in China. Xi came off as a self-confident rising star, and a supporter of private business.

More than a decade later, Xi, now the chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, has launched a broadside against private business in China. Along with tightening regulations governing firms—mandating that companies have Communist Party committees, which can have significant input in their direction, for example—he is also targeting entrepreneurs themselves, as a collective and as individuals.

In September, he directly oversaw the imposition of an 18-year prison sentence, the longest for a political crime since the 1970s, on a real-estate executive who’d criticized him in a private email, according to two Communist Party members with direct knowledge of the case and a source close to the executive’s family—all of whom requested anonymity, fearing retribution. The following month, all indications are that he personally axed what would’ve been the world’s largest initial public offering, that of the financial firm Ant Group. Then, in November, a leading private businessman who ran an agricultural conglomerate, was arrested—ostensibly because of a dispute between his company and a state-owned farm, though a person close to him, who declined to be identified discussing the case, told me he was in jail because he’d spoken in favor of political reform. Finally, until a recent low-key appearance, Jack Ma, the founder of both Ant Group and the e-commerce giant Alibaba, hadn’t been seen in public for months after he criticized the party’s handling of financial reform.

China’s private sector has played an enormous role in its rise. But as Michael Schuman wrote this month in The Atlantic, since Xi took the reins of power in China—first as party boss in 2012 and then as president in 2013—he has moved to reverse much of the country’s economic liberalization of recent decades. The number sequence 60/70/80/90 is used to delineate its contribution: As a rough rule of thumb, private firms churn out 60 percent of China’s GDP, generate 70 percent of its innovation, constitute 80 percent of urban employment, and create 90 percent of the country’s new jobs. Why is he messing with this golden goose? In a word, control.

Despite his chatter to the Americans in 2007, Xi, like many others in the party, has long feared that the private sector could serve as a separate locus of power in China. The bourgeoisie contributed to the fall of Europe’s aristocratic class in the 18th and 19th centuries, and Xi worries that private business in China could play a similar role. He recently told entrepreneurs to model themselves on Zhang Jian, an early-20th-century businessman who made substantial amounts of money not by innovating, but by sucking up to China’s government.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the party wasn’t so paranoid about private business. On July 1, 2001, one of Xi’s predecessors, Jiang Zemin, made a historic speech that welcomed leading Chinese citizens, including entrepreneurs, into the party’s ranks. Even though Jiang wrapped his announcement in party-speak, the word salad didn’t mask the momentousness of the change. Communist China’s founder, Mao Zedong, had stolen private property from the country’s capitalist class and relegated its members to the bottom rung of society. Deng Xiaoping later returned some property and gave entrepreneurs a leg up by acknowledging that with economic reforms some people would “get rich first.” And here was Jiang inviting them to enter at least the margins of political power.

Other developments in the early 2000s gave additional hope that the party was willing to tolerate another domestic pole of power. In government meetings, such as those held by the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, an advisory body, entrepreneurs were becoming increasingly vocal. Behind closed doors, they called on the party to experiment with democracy by letting members choose between candidates for top posts.

In society writ large, businesspeople began to donate money to government-run charities, and when that money was stolen by corrupt officials, they founded their own. Private money went into muckraking media such as Caijing magazine. Pan Shiyi, the chairman of the SOHO real-estate empire, used Weibo, China’s version of Twitter, to bring attention to air pollution, single-handedly popularizing the acronym AQI, or air-quality index. Businessmen and women began organizing civic associations. Entrepreneurs waded into areas that had traditionally been taboo. One privately funded think tank hired the political philosopher Yu Keping, known for his 2009 book, Democracy Is a Good Thing. I witnessed these historic developments while reporting from China for The Washington Post from 1996 to 2003. To call them an explosion of civic-mindedness wouldn’t be an exaggeration.

The turn against entrepreneurs began under Xi’s predecessor, Hu. In the past, private businesses were small—a corner noodle shop or a guy with a local-delivery van. But by the early 2000s, they had begun competing with lumbering state-owned monopolies. Li Beiqi’s noodle shop turned into a nationwide chain called Mr. Lee, while a van driver, Lai Meisong, founded a delivery company and now Forbes estimates his net worth at $6.2 billion. State-owned firms responded by lobbying the government for policies that would help them, not the entrepreneurs. The 2008 global financial crisis validated the belief that China’s state-led economy was superior to the private-led economies of the West. The difficulties faced by capitalist countries, especially the United States, strengthened the argument that peaceful evolution into a more open society and economy, with independent poles of political power, would be a recipe for disaster, for the party and for China. Entrepreneurs, hailed and welcomed just a few years earlier, were now painted as a potential fifth column. Control needed to be reasserted over them and their capital. When Xi took power, he accelerated this campaign.

Yet even by that bleak standard, Xi’s mission to incarcerate the real-estate executive, Ren Zhiqiang, and his maneuvering against Jack Ma reveal the extremely personalized nature of his campaign and highlight his mission to increase the party’s sway over all aspects of life.

Known by the nickname “Big Cannon,” Ren was famed for his bluntness. He’d spoken out against Xi’s views before, contradicting his missive in 2016 that China’s state-run media must be loyal to and serve the party. “Since when has the people’s government turned into the party’s government?” he asked soon after, in a post to his then–37 million Weibo followers. The party responded by placing Ren under investigation. Auditors pored over his accounts in an attempt to finger him for corruption, an old tactic, but found nothing to justify prosecution. Ren’s friends pleaded with him to stop commenting on politics. For a while, it worked: He got into woodworking and exhibited his art at a Beijing gallery in December 2019. The Global Times, a newspaper owned by the party’s Central Committee, even ran a short news item about the show.

Then the coronavirus took hold in Wuhan, China. Parts of the government covered up the news. In February, Xi gave a speech in which he claimed that the party’s handling of the pandemic demonstrated its Communist system’s superiority. Soon after, Ren wrote in a short essay that, watching the speech, he “saw not an emperor standing there exhibiting his ‘new clothes,’ but a clown stripped naked who insisted on continuing being emperor.”

Ren emailed the piece to 11 friends, one of whom leaked it. Ren, his son, and an accountant who’d worked for him were arrested. In jail, according to five sources with knowledge of the executive’s case, Ren was told that unless he admitted to whatever crimes he was going to be accused of, his son would be sentenced to life in prison. Ren was subsequently charged with corruption, even though he’d already been cleared in the 2016 probe. He pleaded guilty. On September 22, a Chinese court sentenced him to 18 years in prison. Ren did not challenge the verdict. The party, however, has yet to keep its side of the bargain: Ren’s son remains in jail.

Ma has not been charged with any crimes, but the handling of his case also reveals Xi’s handiwork. As Ant Group readied for its IPO, Ma made a speech criticizing Xi’s campaign to control financial risks, alleging that it was stifling innovation. Backed by state-owned banks and other financial institutions, which feared Ant, Xi moved to postpone the market debut. Then a team from the party’s feared Disciplinary Inspection Committee showed up at the company’s headquarters in Hangzhou. A news report suggested that Hupan University, a business school co-founded by Ma, could be shut down as part of the party’s policy to reestablish the state’s complete control of education. Desperate to get back in the party’s good graces, Ma reportedly offered state regulators a piece of Ant Group, reflecting a nationwide trend in which state-owned firms gobble up private ones: In 2019, state-owned businesses invested more than $20 billion in private Chinese companies, double 2012’s amount. Then, he vanished, skipping a planned TV appearance and other events, reappearing only last week to speak to a group of teachers during an online event.

Experts such as Dexter Roberts, the author of The Myth of Chinese Capitalism, believe that the economic consequences of Xi’s move to limit private business could be severe. He sees slower growth, weakened innovation, and less competition all contributing to economic stagnation. Already, the lurch back to reliance on state-owned firms has affected productivity: The amount of capital needed to generate one unit of economic growth has nearly doubled since Xi took power.

This attack on entrepreneurs sets China back politically as well. Xi seems to have embraced Leninist logic essentially unchanged since the days of Mao: Only in times of crisis does the party loosen its grip, allowing more free enterprise and more freedom. It always does so reluctantly and then reverts to form.

John Pomfret was the Beijing bureau chief for The Washington Post from 1997 to 2003 and is the author of The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom: America and China, 1776 to the Present.