US optimistic economic sanctions hurting Chinese company in Cambodia

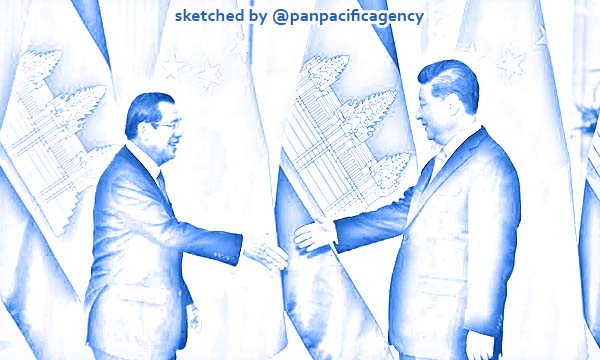

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen (L) shakes hands with Chinese President Xi Jinping before their meeting at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on April 29, 2019. Photo: AFP/Madoka Ikegami/Pool. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

WASHINGTON D.C., Nov 21, 2020, VOA. The U.S. Treasury Department says the economic sanctions imposed under the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act on a Chinese development company operating in Cambodia and its Cambodian liaison are an “effective and appropriate tool” for improving human rights and democracy, VOA reported.

In September, the Treasury Department imposed sanctions on a Chinese state-owned company, Union Development Group (UDG), that operates in Cambodia. The U.S. cited UDG for seizing land and displacing families to make way for a $3.8 billion luxury gambling and lifestyle project in unspoiled Koh Kong province.

UDG operates under a parent company, Tianjin Union Development Group. UDG says the Cambodian project is part of Beijing’s global Belt and Road infrastructure initiative.

A Chinese state-owned entity

In the past, the U.S. raised concerns that the site could be used by Chinese naval forces. Cambodian authorities denied this, pointing to the nation’s constitutional prohibition on allowing foreign troops on its territory.

The U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) designated UDG as a Chinese state-owned entity and alleged that UDG operated as a Cambodian entity under the aegis of Royal Cambodian Armed Forces Gen. Kun Kim, a close ally of Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen. The general allegedly used the military’s right to seize land for its needs to move local people off the land UDG wanted for its resort project.

The U.S. sanctioned Kun Kim and his family network on Dec. 9, 2019, for corruption and bribery.

The U.S. sanctioning of UDG and Kun Kim is pursuant to Executive Order (E.O.) 13818, which builds upon and implements the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act to target serious human rights abusers, their corrupt practices and supporters. The act allows “the executive branch to impose visa bans and targeted sanctions on individuals anywhere in the world responsible for committing human rights violations or acts of significant corruption,” according to Human Rights Watch.

These sanctions, which include freezing funds held in U.S. banks, function as a deterrent “forcing foreign officials at all levels who would use unlawful violence or corruption to consider repercussions from the U.S. government,” according to Human Rights Watch.

The Treasury Department official said accomplices of sanctioned parties could also face consequences.

“Foreign persons who provide certain material assistance or support to the designated entity may be subject to future sanctions by Treasury,” the Treasury spokesperson said.

“We cannot comment on the specific impact that our sanctions have had on UDG, nor potential ongoing investigations,” the spokesperson added.

‘Specific malign actors’

However, during an email exchange in late October, the spokesperson said that “Treasury uses its Global Magnitsky sanctions authority in a targeted fashion to counter the activities of specific malign actors associated with corruption and serious human rights abuse. Targets are carefully investigated, evaluated, and selected based on evidence of their involvement in such activities, as well as our assessment that economic sanctions would be an effective and appropriate tool against them.”

In some cases, the success of a sanction hinges on the “voluntary compliance” of non-U.S. banks.

“The scope of Treasury’s Global Magnitsky sanctions prohibitions is limited to the United States or U.S. persons, but it is possible that other governments may choose to take similar action,” according to the Treasury spokesperson.

Scott Johnston, an associate attorney for human rights accountability at Human Rights First in Washington said, “It’s not uncommon to see voluntary compliance where other foreign companies in banking also choose to comply” with the U.S. Magnitsky sanctions.

“For their own reasons, internal reasons, [foreign banks] look at these sanctions and they do their own internal calculus and decide it’s better for them to be able to maintain positive relationships with the U.S. financial sector than it is to maintain relationships with these actors,” he said.

Once sanctions are in place, a new process begins, Johnston said.

“They [the Treasury] continue to monitor the activities of the sanctioned persons,” he said. “It’s not uncommon to see them do supplemental follow-up sanctions where they will add additional designations” based on additional information unearthed since issuing the original sanction or changes in how the sanctioned person is doing business.

For example, Serbian arms dealer Slobodan Tesic, who was sanctioned in December 2017, faced expanded sanctions in December 2019. After the U.S. agency found companies and people that had helped Tesic evade the initial sanctions, new sanctions were issued to target the enablers.

‘It’ll be stopped’

Olivia Enos, a senior policy analyst in the Asian Studies Center at The Heritage Foundation told VOA Khmer last month that it is not necessary for the sanctioned person to have assets or family members in the U.S. If the sanctioned person uses a dollar-denominated credit card, it doesn’t matter if transactions take place in Cambodia or China, the card will be frozen, she said.

“It’ll be stopped, and it’ll link back to like the bank accounts, too,” Enos said.

She said the sanctions imposed by the U.S. under the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act on UDG and Kun Kim “were very good decisions made by the U.S. government even if some of them were kind of too little and a little bit late. But I think that many of these designations are important.”

Enos continued to say, “I think that the individuals who were chosen were chosen for very specific reasons because in part of their proximity to Hun Sen, but also because of their support of or practices that just distort the flourishing of democracy in Cambodia.”

Enos told VOA Khmer she encourages rights groups to keep monitoring the sanctioned persons and report to the U.S. if there are any changes in their business or other activities.

“I think that human rights advocates and ordinary Cambodian citizens should continue to press for accountability for a government that has taken, you know, what was once at least a semi-democratic system and entirely done away with it,” Enos said. “So I think that there should be no greater pushes for internal accountability, but also that there should be encouragement of future additional sanctions that continue to zero in on Hun Sen and his party.”