After the wave of killing in El Salvador authorities crackdown on imprisoned gang members: Human Rights Watch

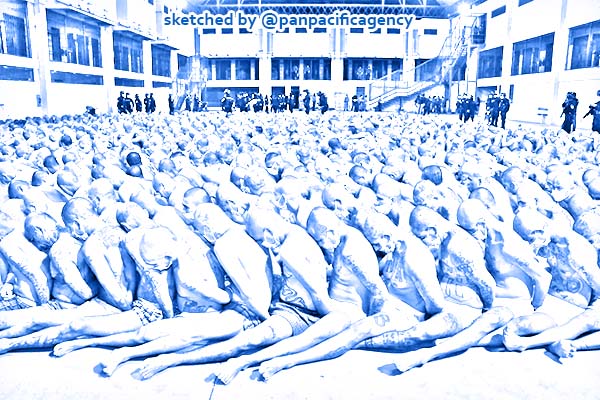

Inmates are lined up at the Izalco prison. (El Salvador presidential press office/AP). Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

SAN SALVADOR, Apr 29, 2020, WP. El Salvador’s government launched a crackdown on jailed gang members as more than 70 people were killed in recent days, a flare-up of violence that ended months of remarkable calm in the Central American country, The Washington Post reported.

Photos released by the office of President Nayib Bukele showed hundreds of inmates stripped to their shorts and jammed together on prison floors while their cells were searched. Some wore face masks, but most had little protection against the possible spread of the coronavirus.

The government appeared to be trying to humiliate and intimidate gang members with the display of toughness, analysts said. But coming amid a pandemic that has triggered strict social-distancing measures in much of the world — including El Salvador — the photos prompted shock and concern about human rights abuses.

“We have the duty to make sure that El Salvador does not become another dictatorship,” tweeted José Miguel Vivanco, head of the Americas division at Human Rights Watch.

Authorities said it was jailed gang members who ordered the killings. Bukele authorized police and soldiers to “use lethal force” against gangs if they or other Salvadorans were under threat. Authorities ordered 24-hour lockdowns in several prisons and affixed metal sheets over cells to ensure gang members could not communicate with one another.

“Not a single ray of sunlight is going to enter any cell,” prisons director Osiris Luna Meza threatened Monday on Twitter.

Human rights organizations have warned about the coronavirus spreading with deadly consequences through Latin America’s notoriously overcrowded detention facilities. Bukele ordered an early and aggressive quarantine in El Salvador, before the country had reported any cases. As of Tuesday it had reported 323 cases and eight deaths.

El Salvador was until recently one of the world’s deadliest countries. Homicide rates soared to 105 per 100,000 people in 2015, according to the World Bank. They fell below 62 per 100,000 two years later.

Criminal groups such as MS-13 and the 18th Street gang still control large swaths of territory. But murders have plummeted under Bukele, and he has enjoyed some of the highest popularity ratings in Latin America.

José Miguel Cruz, an expert on El Salvador’s gangs at Florida International University, said the recent surge in homicides “destroyed the idea that the government has absolute control of the crime situation.”

While authorities claimed that their security policies were bringing down violence, Cruz said, the gangs also played a role. “Gangs didn’t disappear,” he said. “They were there and they continued extorting the population.”

Cruz said the gangs apparently chose to refrain from murders in recent months — but then they decided “to basically kill in a very visible way to attract attention.” Their goal, he said, was unclear.

Political and security analysts have speculated that the sharp decline in violence over the past year reflected some kind of deal between the government and the gangs. Authorities have denied negotiating with gangs.

El Salvador is trying suspects in the notorious El Mozote massacre. The judge is demanding crucial evidence: U.S. government records.

The wave of killings began Friday, with 23 people slain — the most in a single day since Bukele was sworn in last June. It was not immediately evident what touched off the bloodshed. But 13 more people were killed Saturday, 24 on Sunday and 16 on Monday, according to police and local media reports.

The violence was all the more unusual for coming amid the coronavirus pandemic. With Salvadorans ordered into a strict quarantine, there had been an average of two homicides a day since mid-March.

Gangs had even enforced social distancing measures, threatening citizens strolling in the streets without masks.

But while police focused on the coronavirus, authorities said, criminals took advantage.

Government officials said they planned to force members of rival gangs to share cells to inhibit their ability to organize.

“We are going to stop the homicides,” Bukele tweeted Tuesday. “I promise.”

The crackdown led to new accusations that the president was acting in an authoritarian manner. Since the start of the coronavirus outbreak, his government has sent thousands of people to crowded “containment centers,” many of them for violating a mandatory home quarantine.

When the Supreme Court ruled that was unconstitutional, Bukele rejected the decision.

The president’s actions, including the prison crackdown, are “increasing instead of reducing the possibility of contagion,” said Leonor Arteaga, program director at the Washington-based Due Process of Law Foundation.

Bukele’s order allowing greater use of lethal force also came under criticism. The police committed 116 extrajudicial executions from 2014 to 2018, according to the Salvadoran news site El Faro — a period in which the prior government urged security forces to aggressively confront gangs.

David Morales, director of strategic litigation at the human rights group Cristosal, said such orders “generate more violence on the part of the criminals” as well as security forces.

The photographs released by Bukele’s office drew criticism on social media in El Salvador and abroad.

“What cruelty,” former Honduran president Manuel Zelaya tweeted. “It combines a pandemic and brutal and atrocious times that we believed were overcome in history.”

Sheridan reported from Mexico City. Brigida reported from Managua, Nicaragua.