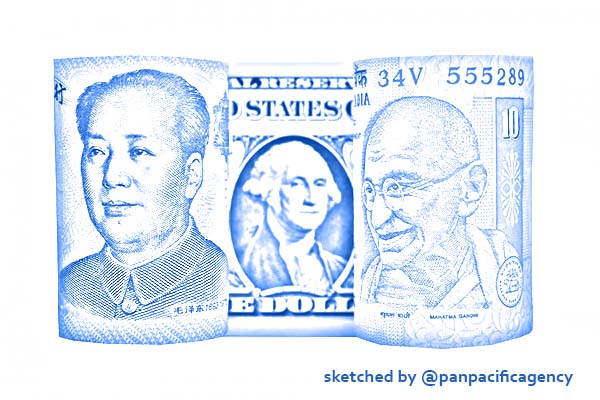

[Analytics] A new balance of power in Nepal’s neighbourhood

Image by The Kathmandu Post / Shutterstock. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

The clichéd maxim of Nepal being a ‘yam between two boulders’ is suddenly erupting into an unknown geopolitical scenario. On the one hand, China is struggling to contain the protests over an extradition bill in Hong Kong, with questions being raised over the ‘one country, two systems’ model of governance that had regulated Beijing’s relationship with the ex-British colony since 1997. On the other, an India buoyed by the resurgence of majoritarian Hindu nationalism has changed the status quo in Kashmir through its brute majority in Parliament and drastic security measures inside the valley. Amish Raj Mulmi specially for The Kathmandu Post.

The two flashpoints hold a lesson for a Nepal that has pushed for connectivity and cooperation between its two big neighbours for its own development process. Hong Kong and Kashmir will test the two giants in their quest to becoming a global power. How the two issues are resolved will be an indication on the way forward for China and India as they adapt to a global environment once again tensed by conflicting objectives and by their own claims to power.

In Ezra Vogel’s monumental biography of Deng Xiaoping, he notes that although Deng was willing to use force—a side which would be seen in 1989 in Tiananmen Square—he preferred to deal with China’s core interests of Taiwan, Hong Kong and Tibet with ‘peaceful means’. The ‘one country, two systems’ policy was systematised in 1982, under which ‘Hong Kong and Taiwan would be allowed to keep their very different social systems in place for half a century or even longer’, while Tibet could also get ‘considerable autonomy’. While things in Tibet changed due to the protests in the 1980s, and the reunification of Taiwan with China remains a distant dream despite Beijing’s continued calls for it, Hong Kong was posited as an example of the success of the ‘one country, two systems’ policy. But Beijing’s willingness had not come from a position of weakness. In fact, Deng had reiterated his willingness to use force ‘as a last resort’ if Britain sent its forces to defend Hong Kong after the lease ran out in 1997.

Beijing warned of ‘signs of terrorism’ in the Hong Kong protests, which is turning into a theatre of the long-drawn confrontation between the US and China. Social media has been abuzz with military vehicles being amassed in Shenzhen, across from the island-city, although there are few indications Beijing will actually mobilise mainland security forces against the protests. In a telling indication, the pro-Beijing Global Times editorial said Hong Kong ‘will not be a repeat’ of the 1989 Tiananmen protests, a remarkable assessment considering the taboo around any discussions on the event. Rather, Beijing will develop Shenzhen as a new economic zone ‘to carry out bolder reforms as a model for other Chinese cities’. An earlier report suggested China was struggling to implement its policies in Hong Kong. Hence the alternative, as Shenzhen lies within the mainland.

The protests have come at a critical time: the trade war with the US shows no signs of yielding from either side, but China’s industrial numbers are the weakest since February 2002. The Belt and Road Initiative, which would have absorbed excess Chinese capacity, is struggling to take off in several countries, including Nepal, especially after talks of a debt trap have made nations wary. The most illuminating example comes from Pakistan. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which would have delinked Beijing’s dependence on its eastern coast, is in trouble. Pakistani officials have suggested Islamabad will have to repay $40 billion over 20 years on investments of $26.4 billion, a figure China disputes. In a parallel to Nepal’s deals with Chinese companies, ‘not a single dollar has entered Pakistani banking channels’. ‘Instead, Chinese banks give the loans to Chinese companies, which buy equipment in China and use it in Pakistan. Consequently, instead of gaining economic benefits, Pakistan is running up huge debts and risking fiscal default.’ Then there are its ‘soft spots’—Xinjiang and Tibet—which have the potential to derail Beijing’s aspirations.

Meanwhile, New Delhi is changing the way it conducts its diplomacy and manages its conflicts, even as it becomes another vital piece in the global balance of power. India had long hailed itself as a ‘soft power’. But the Kashmir move marks the beginning of India turning into a ‘hard power’ stringent about its interests, its critics notwithstanding.

Although the BJP had long argued for the abrogation of Article 370, the international scenario cannot be overlooked. The key takeaway from President Trump’s conversation with Modi earlier this week was that the change in Kashmir’s status is an internal issue for India, with the US signalling no change in its Kashmir policy. A precarious exit from Afghanistan looms for Washington. A new global dynamic is emerging, and the US needs Delhi more than ever to achieve a balance of power vis-a-vis China.

Despite Pakistan’s vociferous protests, the limitations of its foreign policy have been revealed, and its attempts to internationalise the Kashmir dispute at the UN Security Council through China did not succeed. The latter has emerged as the principal voice against Delhi’s Kashmir move, and in a most interesting riposte, Indian external affairs minister S Jaishankar outlined India’s approach to its bilateral relationship by reiterating what has traditionally been Beijing’s line: that ‘differences should not become disputes’. By positing the Kashmir issue as an internal one which will make no additional territorial claims, and by asking Beijing to ‘base its assessment on realities’ in the India-Pakistan relationship, New Delhi has argued for a new paradigm in the bilateral relationship. Rather, India believes China is more concerned about Ladakh, where the border is disputed, than Kashmir. As a former press secretary to the Indian president wrote, while the UK, Pakistan and China have questioned India’s move, Kashmir is just not big enough in the current geopolitical scenario for the global powers to pressure India.

For Nepal, both Hong Kong and Kashmir are important markers that will reveal the contours of the new global order. A shift in global power brings with it disruptions before an equilibrium is achieved. A new balance of power is being realised, and our neighbourhood will be the primary theatre of this shift. Kathmandu needs to closely watch these evolving dynamics.

Amish Raj Mulmi is a writer and publishing professional.