[Analytics] From Russia with guns: why is Southeast Asia buying arms from Moscow, not Washington?

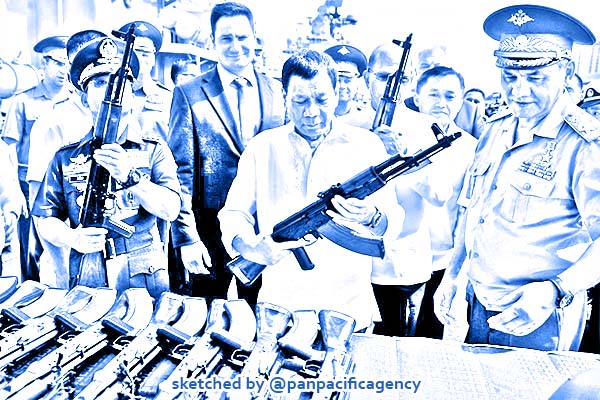

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte holds an AK-47 assault rifle on board the Russian destroyer Admiral Panteleyev in 2017. Photo: Reuters. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

Though it lags only the US in global arms sales, Russia is the top supplier to Southeast Asia, with US$6.6 billion sold between 2010 and 2017. Nations in the region are spending more on defence as a hedge against China’s rise, particularly those involved in disputes in the South China Sea. Meaghan Tobin specially for the South China Morning Post.

Near the People’s Air Force Base in the port city of Vung Tau, Vietnam, a state-of-the-art helicopter engine maintenance and repair facility opened this April to service Russian-made helicopters.

Though Moscow does not often give its arms customers the ability to maintain and repair Russian-made equipment at home, the Vung Tau helicopter facility is part of an effort to broaden the scope of Russia’s prolific arms sales in Southeast Asia.

Viktor Kladov, director for international cooperation at Russian state-backed military industrial giant Rostec, which built the facility, said the firm planned to expand its helicopter repair and support services across the region. Vietnam bought 78 per cent of Russia’s arms exports to Southeast Asia from 2010 to 2017, including six Kilo-class diesel-electric submarines, warships and fighter jets.

Though it lags only the United States in global arms sales, Russia is the top supplier of arms to Southeast Asia. The region bought US$6.6 billion of Russian arms between 2010 and 2017, accounting for more than 12 per cent of Russia’s sales, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (Sipri), a Swedish think tank that publishes global arms tracking data.

Southeast Asian defence purchases from the US over the same period were US$4.5 billion, or about 6 per cent of US global arms sales, according to Sipri. Asia accounted for 40 per cent of total global arms purchases from 2014 to 2018.

Asean nations are bulking up their arms supplies in large part to counter China’s rising influence in the region, analysts say. This is the case particularly for nations with territorial disputes with Beijing in the South China Sea – like Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Russian arms – more than US$54.6 billion of which were exported globally between 2010 and 2017 – are comparatively cheaper than American-made equipment while still being known for their durability. They also come without ideological strings attached – an important value-add at a time when the US and China are jostling for allies and influence.

“Because of rising concerns in Southeast Asia over the past decade about China’s growing assertiveness, such as in the South China Sea, Southeast Asian countries have found it economical to build up their military forces by buying Russian arms,” said former US ambassador William Courtney, now an adjunct senior fellow at Washington think tank the Rand Corporation.

“Russian arms are competitively priced and capable. For example, the Russian air and missile defence system S-400 may be as or more capable than the US Patriot system, but it costs only half as much.”

Arms have flowed into Southeast Asia over the past few years in part because Asean nations can now afford to buy them. Siemon Wezeman, senior researcher at Sipri, said that following their substantial economic growth over the past several decades, more Asean nations felt they could afford larger militaries.

Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and even US defence treaty allies Thailand and the Philippines have looked into making purchases from Russia.

Unlike the US, Russia offers arms and military equipment without scrutiny of what purchasers plan to use them for, or their records on human rights abuses.

In Indonesia, which accounted for 10 per cent of Russia’s arms sales to Southeast Asia since 2010, the memory lingers of Washington freezing defence funding over human rights abuses in East Timor and West Papua. According to Wezeman, this keeps Jakarta wary of relying too heavily on any one nation for arms and equipment.

Indonesia is buying equipment for non-military purposes too, experts say – fighting drug and human trafficking as well as illegal fishing activity across its vast territorial waters.

“Think about how big some of these nations are. Indonesia occupies an area about the size of Europe, to do adequate disaster relief or fisheries patrols requires a substantial amount of equipment,” Wezeman said.

Another benefit of buying from Russia is flexibility of payment. In another practice that sets it apart form the US, Russia sometimes allows its customers to purchase arms with palm oil or other commodities priced below market rates.

And, as evidenced by Vietnam’s new helicopter engine facility, Russia may be moving to invest more in providing maintenance capabilities to its customers, though experts caution that Russia may not have the resources to follow through on some of its promises of upgrades and repair over the lifespan of the equipment it sells.

The Royal Malaysian Air Force is also studying a proposal to buy Russian-made Sukhoi fighter jets to upgrade its current aircraft. Nations like Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia had some options in their arms purchases, Wezeman said. “They’re wary of becoming dependent on one supplier and want to see what type of promises will come with [their purchases].”

However, Russian arms come with the threat of penalties from the US, which passed a 2017 law to sanction any country which buys from companies linked to Russian military or intelligence entities.

Though US President Donald Trump can technically ask Congress for exemptions to the sanctions for countries which are friendly to America and buy arms from Russia, the exemption does not apply to large purchases.

In 2016, after Congress criticised President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs, the US called off the sale of 26,000 assault rifles to the Philippines.

One holdout on Russian arms purchases is Singapore, which has one of the region’s best-equipped militaries and has strong security ties with the US.

Both sides recently renewed a three-decade-old pact that grants US forces access to the Lion City’s naval and air bases. Earlier this year, Singapore announced it would buy four US-made F-35 fighter jets, choosing these over competing warplanes from Europe and China.

Analysts say the US sanctions could be a boon for Beijing, preventing Southeast Asian nations from acquiring the deterrence capabilities they are looking for.

China sold only US$1.8 billion in arms to Southeast Asia between 2010 and 2017, 66 per cent of which went to Myanmar, according to Sipri.

But with Malaysia shopping for warships from China and Thailand shopping for submarines, experts say these numbers are sure to increase.