[Analytics] Why Chinese-speaking tour guides don’t mourn Chinese absence in Russia now

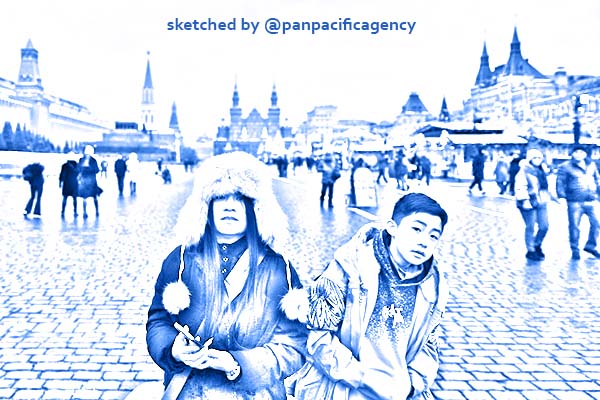

Chinese tourists in Red Square, Moscow. Photo: Sergei BobylevTass via Getty Images. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

Until the coronavirus pandemic shut tourism down, half the foreign visitors to Russia were from China. Now they’ve all disappeared, leaving empty streets. Chinese-speaking Russian tour guides don’t mourn their absence, having already been edged out by cut-price Chinese operators. Pavel Toropov specially for the South China Morning Post.

Until a few months ago, roughly half of all foreign tourists in Russia were Chinese. Then, in January, Chinese tour groups vanished from the streets of Moscow and St Petersburg after Russia banned the entry of Chinese citizens following the coronavirus outbreak.

The introduction of visa-free entry for Chinese tour groups in 2015 set off an explosion of Chinese tourism in Russia, their number surpassing two million visitors in 2018, according to the Chinese Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

While the pandemic is a catastrophe for the country’s tourism industry, one group is indifferent to the losses the absence of Chinese visitors will cause – Russian tourism businesses that once benefited from their influx but which, local guides say, have been squeezed out of the market by Chinese operators who cut prices and corners.

For these businesses, even before the outbreak the Chinese bonanza was nothing like what they had hoped for.

Few Chinese-speaking Russian guides lament the sudden disappearance of Chinese tourists. On the contrary, they hope that by the time the Chinese return, a law will have been passed which allows only Russian citizens to work as guides. That way, they can earn a living from Chinese tourism once more, while Chinese visitors can again enjoy high-quality, rather than bare-bones, tours.

The popularity of Russia as a destination stems from the affection that many Chinese – especially the older generation – feel for the country. The Soviet Union was once China’s Big Brother, and educated Chinese tend to be well versed in Russian literature and history.

Arina Levental is a licensed Chinese-speaking guide in St Petersburg. She started working with the first Chinese tourists who began to appear in Russia in the 1990s. Levental used to work for Katyusha, a major tour operator specialising in Chinese tourism. Despite the boom that followed the granting of visa-free entry for Chinese, Katyusha went bankrupt in 2016, unable to compete with the rock-bottom prices offered by its new Chinese competitors.

For a tour group to be given visa-free entry into Russia, it must be put together by an official travel agency in China, Levental, who now works with Russian and European tour groups, told the Post.

Once in Russia, every such group must then be received by a licensed domestic tour operator, who is paid for their services. The Chinese diaspora in Russia quickly set up their own tour operations and started to drive prices down.

“The price of a one-week trip to Russia is now about US$1,000, all inclusive,” says Polina Rysakova, a Chinese-speaking guide with 20 years of experience. “A laughable amount.”

Rather than charge for their services, the diaspora-owned tour operators pay travel agencies in China for each group sent over. To make money, tour operators then pass their costs on to so-called grey guides.

“It is essentially a pyramid scheme,” says Rysakova. Chinese tour operators in Russia put out adverts to recruit fellow members of the Chinese diaspora as guides, luring them with promises of huge commissions on their groups’ purchases of cosmetics, amber and gold, she says.

The guides are charged a fee by the tour operator – between US$15,000 and US$20,000 per season. On top of that they have to pay “pillow tax” of about US$20 for every member of every group. If they cannot pay upfront, this becomes debt. The grey guides then mercilessly drag their groups through souvenir shops, most of which are now also owned by the Chinese diaspora. Thirty per cent of all the group’s purchases is the guide’s standard commission.

“Many find themselves in debt to the tour company at the end of the season.” says Rysakova. “We see announcements in Chinese of guides selling cars, even flats, to pay those debts.” The following season, new guides are recruited.

Professional Russian guides refuse to work under this scheme, and non-salaried employment is illegal under Russian law. Over the past few years, 400 Chinese-speaking licensed Russian guides lost their jobs, according to Rysakova.

It is very difficult for the authorities to prove that a grey guide is actually in paid employment, explains Rysakova. With fellow guides she recently started a Laboratory for the Study of Chinese Tourism. They identify grey guides and try to expose their activities.

Llevental says: “There are also Chinese guides who finished university in Russia, live here and speak excellent Russian. They are great guides. But Chinese companies do not like them because they refuse to work to their conditions.”

“Travel companies need swindlers, not guides,” says one such former guide who preferred to remain anonymous. “The market may be expanding, but only a small number of people involved can make any money.”

According to an investigation by a St Petersburg media portal, fontanka.ru, a street in St Petersburg is lined with amber shops that only Chinese tour groups are allowed to enter. A Russian face would quickly be asked to leave by security. Prices in the shops are astronomical and the authenticity of the products highly questionable.

Grey guides in St Petersburg work together with amber shop owners and “zombify” their groups with non-stop stories of the miraculous curative properties of amber: “Must-buy-amber!” says Levental, laughing.

Now, with no Chinese tourists on the streets, these amber shops are closed.

Levental predicts that once the restrictions on Chinese citizens are lifted, it will take up to two years for the number of Chinese tourists to return to pre-outbreak levels.

Overpricing by “grey guides” is the norm. “There is a cheap Russian cosmetics brand, Babushka Agafia – a mask sells for 50 roubles (64 US cents), but the guides resell it for 500,” she says. “Every tourist is given a list – you tick what you need, give the quantity and it is couriered to your hotel that evening.”

The hard-done-by Chinese tourists do value a real guide. “Many tell me that they are just being dragged through shops and are learning nothing about the city,” says Levental.

More than 1,000km north of St Petersburg, in the Russian Arctic, lies one of Russia’s newest tourist attractions – the village of Teriberka. The internationally acclaimed 2014 film Leviathan was filmed here and its release triggered a tourism boom, drawn by Teriberka’s spectacular Arctic landscapes and the northern lights.

Vladimir Onatsky, the president of the local Association of Arctic Guides, describes pre-outbreak Chinese tourism as “a tornado”, and says that it has been a force for good.

“Five years ago, there was nothing here. The main development engine came from Chinese tourism,” says Onatsky.

Last year 20,000 Chinese came, Onatsky estimates, mainly to see the northern lights. The once dilapidated fishing village now has a craft brewery, coffee shops, and a boutique-style hotel.

Yet, even in the remote Arctic, Russian operators were already losing the Chinese sector. “Until last year, the Chinese used Russian bus companies to bring their tourists from Murmansk. Now there are 28 buses operated by a single Chinese-owned company from St Petersburg. Their rates are somehow a third of what a Russian company charges,” Onatsky says.

Again, it is the Chinese customer who ultimately bears the cost.

“My fully guided tour in a 4×4 is 12,000 roubles for four people, coming from Murmansk,” says Onatsky. “Some Chinese arrange normal taxis from Murmansk for 3,000. They have no guide and no idea what they see. The drivers do not know the road, which is in a terrible condition. We end up pulling their cars out of roadside ditches.”

The coronavirus has hit Onatsky’s business too. “The season for the northern lights starts in September and ends in March, so we only lost February and March. Even though we work mainly with Russian and European tourists, my company already lost more than US$10,000 of Chinese business this season.”

Onatsky hopes that when the season starts again in September the Chinese can come back. He runs high-end photography tours from China: “Great to work with!” says the Russian.

But an amber shop aimed at Chinese tourists has recently opened in Teriberka, he adds. “Amber zombifying” may have spread to the Russian Arctic, but for now at least, it is kept in check by a very real virus.