[Analytics] Pandemics, protests and policymaking in Central Asia

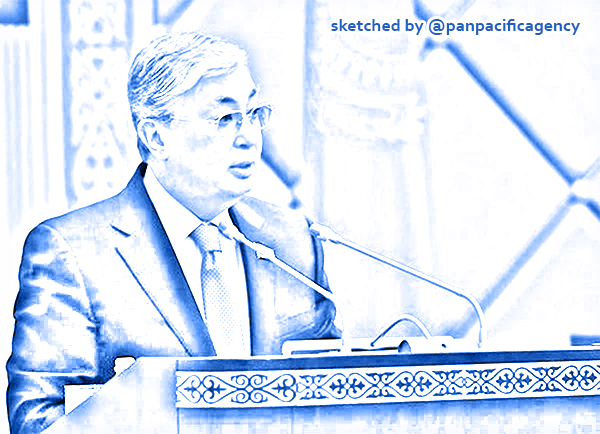

Kassym-Jomart Tokayev took over as Head of State following presidential elections in Kazakhstan. Photo: Modern Diplomacy. Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

In 2021, the five Central Asian republics celebrated 30 years of independence. They may not have fought for emancipation from the Soviet Union, but Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan have achieved genuine statehood and learned how to survive as sovereign nations. Their political and economic systems, while lacking in freedom, matured enough to safeguard against pressing existential threats. Kirill Nourzhanov specially for the East Asia Forum.

These accomplishments were put to the test in 2021 against the common background of the COVID-19 pandemic. In January 2021, the President of Tajikistan prematurely announced victory over COVID-19 in his country. In the second half of the year, Central Asia struggled with a new wave of infections, reaching one and a half million cases and 22,000 deaths among the combined population of 74 million.

The government of Turkmenistan continues to deny any cases or deaths, but independent reports suggest it had not escaped the morbid effects of the pandemic. Compared to 2020, economic recovery had kicked in, but high inflation and low vaccination rates meant the most vulnerable strata still faced food insecurity, uncertainty and limited employment opportunities.

Authoritarian political stability remained largely intact across the region. Kyrgyz leader Sadyr Japarov, who came to power in the wake of street protests in October 2020, consolidated his rule by winning the presidential poll in January 2021. He pushed through a constitutional referendum expanding his prerogatives in April and secured a favourable outcome in parliamentary elections in November 2021.

The only serious domestic crisis in Tajikistan involved protests in the perennially unsettled Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region in November, which subsided after four days of tense negotiations with central authorities. President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov of Turkmenistan advanced plans for a dynastic succession while engaging in habitually eccentric behaviour. Presidential elections in Uzbekistan returned Shavkat Mirziyoyev to office with a slightly reduced share of votes despite the absence of real opposition.

Throughout 2021, there were few signs of major trouble in Kazakhstan. The January parliamentary elections demonstrated general popular acquiescence to the regime while also indicating some tension between the two poles of executive power: President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev and former president Nursultan Nazarbayev. Although the former president formally resigned in 2019, he retains significant formal and informal authority.

In early January 2022, this intra-elite tension suddenly led to what Tokayev characterised as a coup attempt and ‘massive crisis’ — the worst in over 30 years of independence. A detailed picture of the objectives and drivers behind the large-scale violence in Almaty and other cities is yet to emerge, but it is clear that the tandem authority is no more, with Tokayev firmly in charge.

One of the most intriguing questions for 2022 and beyond is whether the abrupt end of the post-Nazarbayev transition will lead to systemic reforms rather than mere executive personnel change and redistribution of wealth. Tokayev’s first state of the nation address after the crisis appeared to point to the latter.

At the regional level, the Third Consultative Meeting of the heads of state of Central Asia held in August 2021 advanced the agenda of pragmatic cross-border cooperation despite not producing any ground-breaking initiatives. Importantly, all serving presidents took part despite a series of armed clashes over land and water between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan earlier in the year. The informal summit resolved to pay greater attention to people’s diplomacy and especially dialogue among women to expedite mutual trust and understanding in Central Asia. There was a tactical acknowledgment that state-to-state regionalism progressed with difficulty.

The crisis in Afghanistan dominated the Central Asian states’ international agenda. The US withdrawal and speedy demise of the Ghani government in Kabul in August 2021 was a surprise. The rapid and comprehensive victory of the Taliban heightened the concerns of Central Asian states about security threats from the south. Chief among these threats is terrorism. Reflecting a widely shared perspective, the President of Tajikistan warned about 6000 militants in northern Afghanistan loyal to the so-called Islamic State militant group and connected with the jihadi underground in Central Asia. There are fears that the militants could rapidly destabilise local governments.

The region’s leaders responded to this challenge in two ways. With the partial exception of Tajikistan, they quickly built functional relations with the Taliban government promising aid, trade and potential recognition in return for the suppression of international militants. They also pursued tighter military and security cooperation with Russia and China while turning away from ‘an unreliable, uncommitted United States’.

In 2022, managing COVID-19 and instances of popular discontent will be priorities for the Central Asian governments. The recent riots in Kazakhstan are unlikely to lead to greater liberalisation and the tightening of social control is expected. None of the countries has national elections planned for 2022, which removes some triggers for protest. A resumption of border hostilities between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan cannot be ruled out. The one guarantee for Central Asia in 2022 is that the situation in Afghanistan will continue to be at the centre of the region’s foreign and security policymaking.

Kirill Nourzhanov is a Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies, the Australian National University.