[Analytics] The costs of carving up Papua

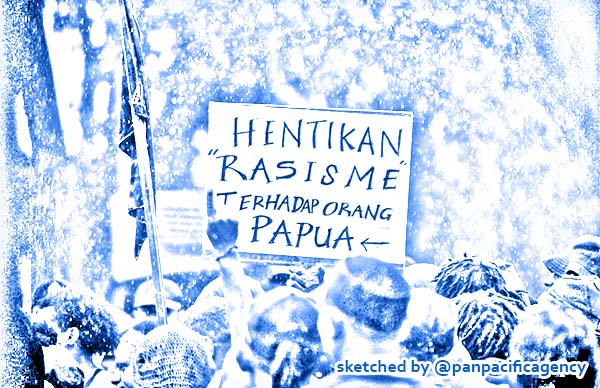

Students participate in a rally in Bandung, West Java, on Tuesday to protest racism against Papuans and call on the government to arrest those involved in besieging a dormitory occupied by Papuan student in Surabaya, East Java, nearly two weeks ago. (Antara Photo/Raisan Al Farisi). Sketched by the Pan Pacific Agency.

Policymakers in Jakarta are forging ahead with a plan to divide Papua into four provinces despite strong local opposition. Jakarta claims this will accelerate development and bring the government closer to the people because the new provinces will be based on indigenous cultural zones. But Papuans see it as a move to exploit regional political divides instead of addressing human rights abuses and the marginalisation of indigenous Papuans. Deka Anwar specially for the East Asia Forum.

The central government has long advocated for dividing Papua into multiple provinces to contain the threat of separatism. But after Suharto’s fall in 1998, Jakarta was in no position to follow up on this. In 2001, the government passed a law on special autonomy to quell demand for a referendum. It stipulated that new provinces must be approved by provincial administrations, including the Papua People’s Council.

Then in 2003, former president Megawati Sukarnoputri split Papua into West Papua and the Papua provinces without consulting the Papua People’s Council. This was in clear violation of the law and deepened Papuan distrust of Jakarta. Further discussion on new provinces was halted after Lukas Enembe became governor of Papua in 2013. Enembe blocked petitions from local politicians to form North and South Papua provinces because it would diminish his power and revenue from resource-rich mining sites.

In 2021, the plan for new provinces was revived after Indonesia’s parliament passed a revised special autonomy law, stripping the Papuan governments authority to approve a new province. Its adoption, over strong protest from many Papuans themselves, coincided with an ill Enembe and the deputy governor Klemen Tinal’s death. In April 2022, parliament initiated proposals for four new provinces — North Papua, Central Papuan Highland, Central Papua and South Papua.

Carving up Papua primarily benefits the central government in Jakarta and local government elites. Jakarta can deliver grants and projects more easily and work with smaller provinces and regencies to monitor their implementation. New administrative units would also justify a greater budget for the military and police to build more territorial bases and recruit more personnel.

Local elites who will fill the new provincial administrations expect dividends from government projects and foreign investments. Revenue from sub-regional projects would no longer have to be shared with other regions. Central Papua, which would have six regencies, will keep the bulk of revenues from the Freeport copper and gold mine in Mimika and the US$15.4 billion Blok Wabu gold mine in Intan Jaya. Local elites are also eager to accelerate the creation of new provinces so they can participate in the 2024 elections.

Public opinion about the new provinces is divided along ethnic-regional fault lines. Staunch opposition comes from communities in the central highlands — the mountainous region stretching from Nabire regency to Pegunungan Bintang. This area is the stronghold of Enembe, the former regent of Puncak, and where some of the deadliest riots against the new provinces took place.

Meanwhile, Papuans living in coastal regencies have long clamoured to have their own provinces. Since Dutch colonial rule, Papuans from northern regencies such as Yapen, Biak and Jayapura had dominated provincial politics. The trend shifted in favour of highlanders after Enembe won the governorship in 2013. Highland politicians also benefit from the noken voting system, traditional voting by proxy, which is widely practised in the remote highlands. The system is supposed to help address infrastructure shortcomings, but has been criticised for its lack of transparency and voter fraud.

Separating from the highland region will allow coastal politicians to reclaim influence by governing North Papua with the capital in Jayapura.

Crucially, the new provinces are unlikely to solve the problems of violent conflicts and separatism. Papua faces multifaceted security problems from armed insurgency, indigenous-migrant tensions, intra-Papuan polarisations, electoral violence and land conflicts.

Elections in Papua province have long been characterised by violence and electoral fraud. Adding new administrative units may intensify tensions between neighbouring tribes that are now vying for resources and positions in new provincial administrations.

Papuans fear that the new provinces would open the floodgate of non-Papuan public servants filling the new bureaucracies. The migrant population has surpassed the number of indigenous people and occupies political positions in better-developed coastal regencies. In the 2019 election, only 13 out of 40 legislative seats were won by indigenous Papuans in Jayapura and 3 out of 30 seats in Merauke. In the same year, anti-racism protests in several regions turned into communal conflict targeting migrants.

The new provinces are not likely to curb the growing strength of the West Papua National Liberation Army. The armed insurgency has now expanded from a concentration in four to eleven regencies, including in Maybrat, West Papua.

Despite visiting Papua more than any of his predecessors, Indonesian President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo’s policies in Papua have neglected Papuans’ demand for inclusion in policymaking. Instead of bulldozing its way to creating new provinces, Jakarta should engage in meaningful consultation with the Papuan people — or risk strengthening demands for independence.

Deka Anwar is Research Analyst at Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPAC).